Title: Disseminated cryptococcosis in a patient treated with ibrutinib

Submitted by: Sibylle C. Mellinghoff, MD

Institution: University Hospital of Cologne, Department of Internal Medicine

Email: sibylle.mellinghoff@uk-koeln.de

Date Submitted: 04.06.2020

History: A 75-year old women presented with fever and an unproductive cough which had been present for seven days. She had chronic lymphatic leukemia which was currently successfully treated with ibrutinib for almost one year.

Physical Examination was unremarkable except for a temperature of 38.6 C.

Upon admission, she was started on ceftriaxone and gentamicin as empiric therapy. Despite the antibiotics, she remained febrile and after four days, she developed severe respiratory failure and was intubated.

Laboratory Examination at admission: Elevated C-reactive protein (253 mg/dl), leukopenia (1.200/µl)

Question 1: What are probable/possible diagnoses?

The most likely diagnosis was community acquired pneumonia in an immunosuppressed host. Since patient is on ibrutinib, a broad range of opportunistic infections should be considered including fungal infections, including molds.

Also, blood stream infections were considered. Due to treatment with ibrutinib, fungal infections were also a possible differential diagnosis.

Diagnostic Tests Performed:

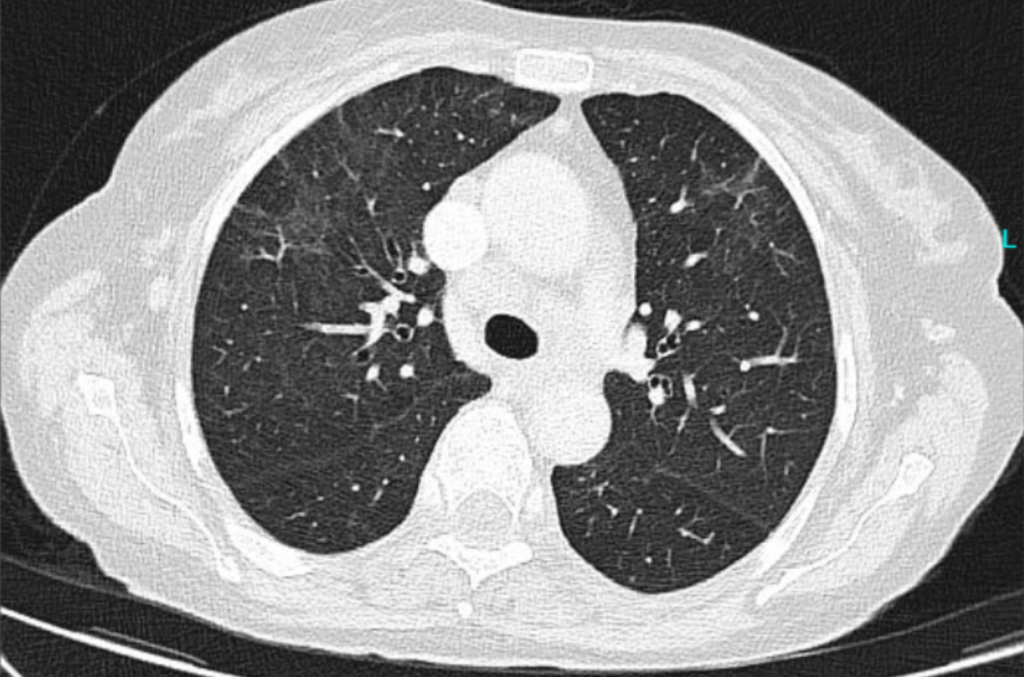

- Two chest CTs: The first was performed two days after hospital admission (Figure 1A),

- Blood cultures: (+) for yeast.

- Bronchoalveolar lavage: No relevant pathogen.

- Lumbar puncture

- Cryptococcal angigen (Blood and CSF)

Blood cultures revealed fungemia that was later identified as Cryptococcus neoformans. This was also shown in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). From the microbiological perspective, Cryptococcus spp. are yeast-like and have to be distinguished from further yeasts.

Cryptococcus antigen was found positive in CSF and serum.

Bronchoalveolar lavage was unremarkable.

Final Diagnosis: Disseminated cryptococcosis (including blood stream infection, CSF infection, as well as possible infection of the lung)

Question 2: What treatment is recommended in the care of this patient?

Treatment: The patient received ceftriaxone and gentamicin as empiric anti-infective treatment for fever of unknown origin. When blood cultures were found to be positive for Cryptococcus spp., treatment was adjusted. As induction therapy the patient was treated with liposomal amphotericin B and (3 mg/kg per day) flucytosine (100 mg/kg per day) for 4 weeks. After 8 days of therapy, the patient was successfully extubated.

Thereafter, she was treated with fluconazole 400 mg/day, which was reduced to 200 mg/day after two months and continued for another 12 months. Ibrutinib treatment was stopped and the patient received venetoclax thereafter. She was discharged from hospital after 4 weeks and after 6 more weeks in a rehabilitation center she had fully recovered.

Outcome: Lumbar punctures after 2 and 4 weeks did not show any CSF pathogen. A second CT was performed 4 weeks later (after 3 weeks of appropriate treatment for cryptococcosis) (Figure 1B).

Discussion:

We here report a case of disseminated cryptococcosis during treatment with ibrutinib for CLL.

During the natural course of CLL, patients frequently have numerous infectious complications. Those are mostly attributable to an impaired humoral immunity and T-cell response. The Bruton Tyrosine Kinase (BTK) regulates B-cell activation, interaction, and survival by regulating B-cell receptor signaling 1. Additionally, BTK has been identified as a direct regulator of essential elements in innate immunity, e.g. regulating recruitment of neutrophils, monocytes and macrophages 2. Hence, therapeutic targeting of BTK in the CLL patient population increases the risk of opportunistic infections. Especially, invasive fungal infections (IFI) which have recently been described by several investigations 3-7. Due to diverse risk factors and pre-treatments of ibrutinib recipients, the clear association of ibrutinib and IFI remains difficult. The effect of ibrutinib on macrophages seems to be important: Inhibition of the macrophage Toll Like Receptor9–BTK–calcineurin–Nuclear Factor signaling pathway leads to an immune defect increasing the innate immune system’s susceptibility to IFI 8.

To date, the European Conference on Infections in Leukemia (ECIL) and the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) have authored position papers regarding infectious complications under ibrutinib treatment 9,10. However, clear recommendations regarding indication for IFI prophylaxis have not been published due to the lack of data. Further evidence for the use of fungal prophylaxis is needed not only in patients on ibrutinib therapy, but all recipients in which novel targeted antineoplastic agents are used.This case is another example of an IFI during ibrutinib treatment. It shows the importance of considering rare opportunistic infections in those patients that are treated with novel targeted antineoplastic agents. Physicians should be aware of this potential risk in these compromised patients and make sure to include IFI in their differential diagnosis of fever.

Key References:

- Satterthwaite AB, Witte ON. The role of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase in B-cell development and function: a genetic perspective. Immunological reviews. 2000;175:120-127.

- Weber ANR, Bittner Z, Liu X, Dang TM, Radsak MP, Brunner C. Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase: An Emerging Key Player in Innate Immunity. Frontiers in immunology. 2017;8:1454.

- Grommes C, Younes A. Ibrutinib in PCNSL: The Curious Cases of Clinical Responses and Aspergillosis. Cancer cell. 2017;31(6):731-733.

- Ghez D, Calleja A, Protin C, et al. Early-onset invasive aspergillosis and other fungal infections in patients treated with ibrutinib. Blood. 2018;131(17):1955-1959.

- Chamilos G, Lionakis MS, Kontoyiannis DP. Call for Action: Invasive Fungal Infections Associated with Ibrutinib and Other Small Molecule Kinase Inhibitors Targeting Immune Signaling Pathways. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2018;66(1):140-148.

- Varughese T, Taur Y, Cohen N, et al. Serious Infections in Patients Receiving Ibrutinib for Treatment of Lymphoid Cancer. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2018;67(5):687-692.

- Fürstenau M, Simon F, Cornely OA, et al. Invasive Aspergillosis in Patients Treated With Ibrutinib. Hemasphere. 2020;4(2):e309. Published 2020 Feb 13. doi:10.1097/HS9.0000000000000309

- Herbst S, Shah A, Mazon Moya M, et al. Phagocytosis?dependent activation of a TLR9–BTK–calcineurin–NFAT pathway co?ordinates innate immunity to Aspergillus fumigatus. EMBO Molecular Medicine. 2015;7(3):240.

- Reinwald M, Boch T, Hofmann WK, Buchheidt D. Risk of Infectious Complications in Hemato-Oncological Patients Treated with Kinase Inhibitors. Biomark Insights. 2015;10(Suppl 3):55-68.

- Maschmeyer G, De Greef J, Mellinghoff SC, et al. Infections associated with immunotherapeutic and molecular targeted agents in hematology and oncology. A position paper by the European Conference on Infections in Leukemia (ECIL). Leukemia. 2019.