Skin lesions in a patient with acute myeloid leukemia presenting with febrile neutropenia

Submitted by: Amy Spallone, MD; Dimitrios P. Kontoyiannis, MD, ScD, PhD, FACP, FIDSA, FECMM, FAAM, FAAAS

Institution: The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center

Email: aspallone@mdanderson.org

History:

40-year-old male admitted for fevers of one-week duration and neutropenia. His past medical history was significant for acute myeloid leukemia diagnosed one year prior, now relapsed and refractory to salvage chemotherapy. One month prior to admission at MD Anderson, he was admitted at an outside hospital for weakness and fevers. During that hospitalization, two nodular lesions were discovered on his back, which were treated with oral doxycycline without improvement. On current admission, these lesions were present and per patient had grown in size, now with central necrosis.

Medications:

His outpatient, prophylactic antimicrobial regimen included the following: posaconazole 300mg daily extended release tablets, valacyclovir 500mg daily, levofloxacin 500mg daily.

On admission, he was continued on posaconazole and valacyclovir. Levofloxacin was held and he was started on intravenous daptomycin 6 mg/kg daily and piperacillin-tazobactam 3.375g Q6H for febrile neutropenia.

Social History:

He is from the Midwest and denied recent international travel, animal exposures, or outdoor hobbies and activities. Prior to becoming sick, he worked in construction. He has several old tattoos acquired at a tattoo parlor that adhered to sterilization and sanitation regulations.

Physical Examination:

BP: 104/64

Pulse: 90

Resp: 20

Temp: 39.5 ?C

SpO2: 96% room air

GENERAL: In no distress, well appearing

HEENT: PERRL, anicteric, EOMi, oral mucosa moist w/o ulcers/thrush; Good dentition

NECK: Full ROM, no rigidity or pain on flexion

CVS: RRR, normal S1S2; No murmurs or rubs; No bipedal edema; Warm and well perfused extremities

RESP: CTAB w/o wheeze or rhonchi, exam-induced coarse cough

BACK: no point tenderness over spine, no CVA tenderness

GI: Abdomen was soft and non-tender; no gross organomegaly

SKIN: 2 lesions present on back w/central necrosis and erythematous boarder. He had several tattoos.

MUSC: No gross deformity, no limitation of ROM

NEURO: AAO w/o focal neurological deficits present on exam

Right chest port-a-cath present w/o surrounding erythema or pain on palpation

Laboratory Examination:

CBC:

WBC 0.1 (ANC: 0.5, ALC: 0.8)

HGB 6.3

Plt 26.0

INR 1.0

CMP:

NA 142

K 3.9

CL 107

CO2 25

BUN 16

sCr 1.37

T bili 0.4

AST 32

ALT 20

Alb 1.37

Posaconazole serum level: 3890

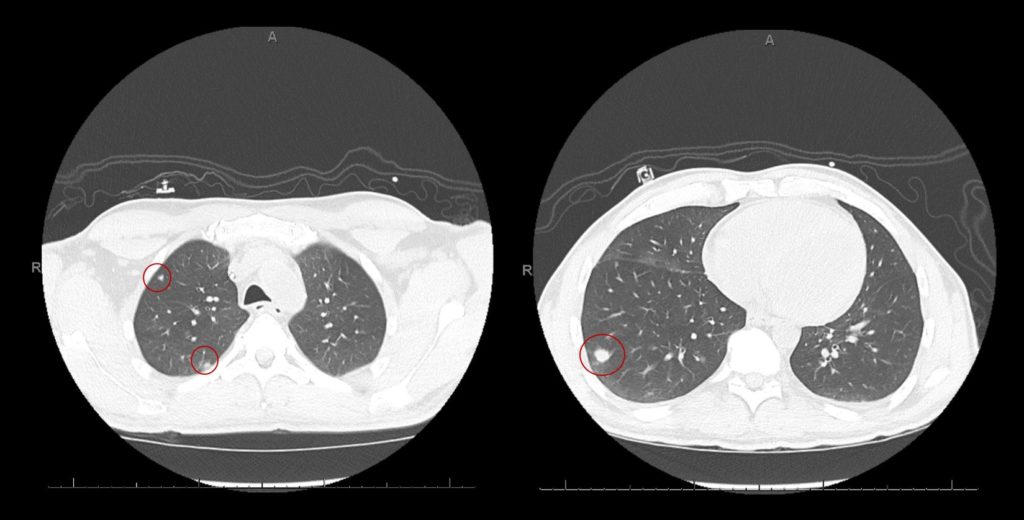

Radiology: CT Chest non-contrast

Bilateral lung nodules were suspicious for fungal infection. Some of the nodules have a halo of ground glass but without cavitation.

What are probable/possible diagnoses?

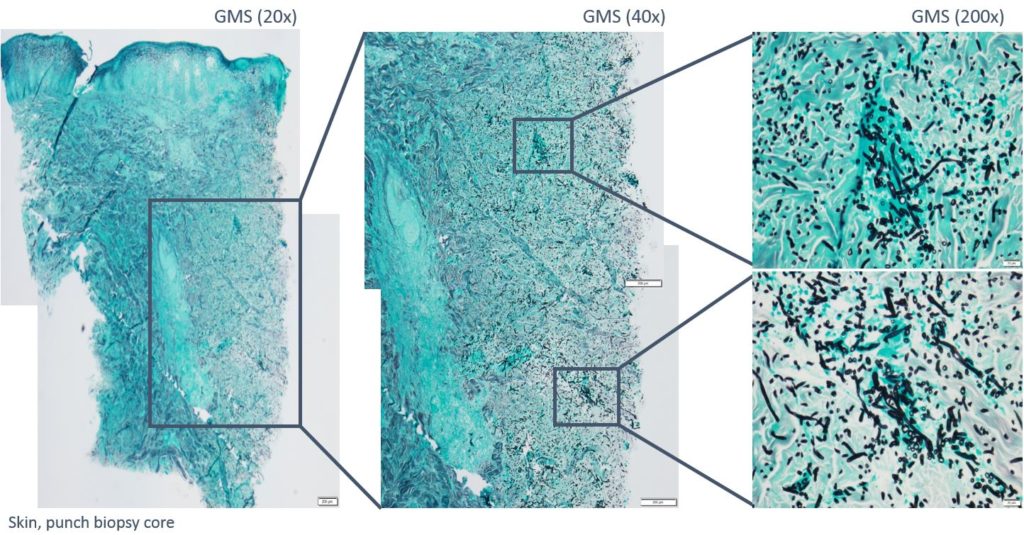

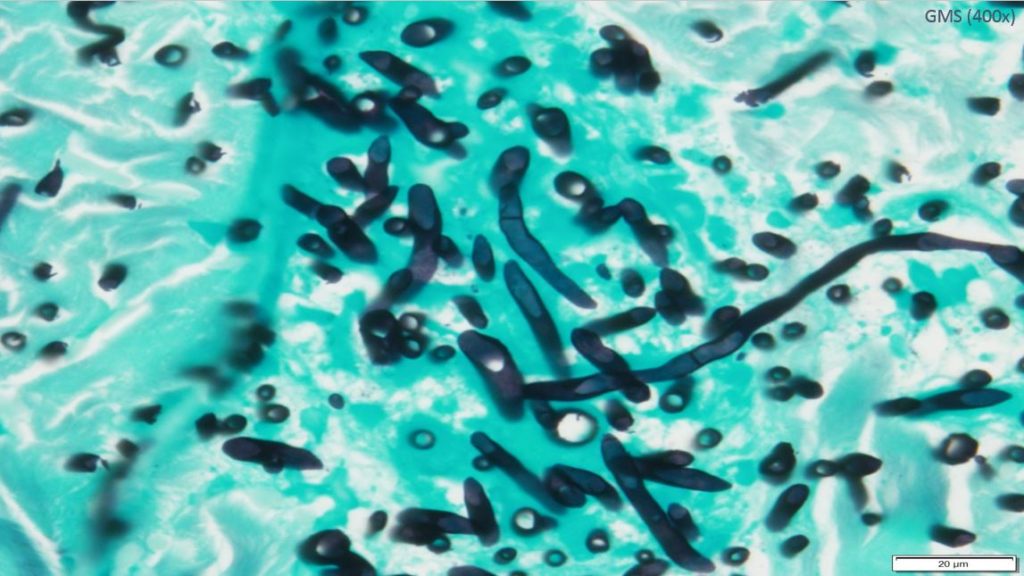

Microbiology/Diagnostic Tests Performed: Bronchoscopy with lavage: routine and fungal cultures of bronchoalveolar fluid failed to grow any organisms. Left upper back, skin punch histopathology: Deep fungal septate hyphae with angioinvasion. Gomori methenamine silver stain highlighted numerous fungal organisms. Fite and Gram’s stains were negative for bacteria, including acid-fast bacteria. Immunohistochemical studies for Rhizopus and Aspergillus were negative. Skin punch culture: Mold isolated

Identification confirmed as: Fusarium species

Results of Antifungal Susceptibility Testing:

Method: CLSI M38

Performed by: UT MD Anderson Cancer Center

Division of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

1515 Holcombe Boulevard

Houston, TX 77030

| Drugs: | mcg/ml | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Amphotericin B | 0.5 | No established Breakpoints |

| Posaconazole | >16 | No established Breakpoints |

| Voriconazole | >16 | No established Breakpoints |

Final Diagnosis: Disseminated fusariosis

What treatment is recommended in the care of this patient?

Treatment: Intravenous Liposomal amphotericin B 5 mg/kg daily for two weeks tapered to 5 mg/kg three times per week for two weeks along with oral voriconazole 300mg Q12H for an undetermined duration pending neutrophil count recovery.

Outcome: The patient was discharged home in stable condition to continue his liposomal amphotericin B infusions at home for four weeks. He returned for an outpatient follow up one week after discharge, however he was lost to follow up thereafter.

Discussion: (500 words)

Fusarium is a large genus of ubiquitous, environmental molds commonly found in soil and plant debris. In humans, a few clinically important Fusarium species cause a broad range of infections, such as superficial (keratitis and onychomycosis), locally invasive (burns and wounds), and disseminated disease.1 Severity of infection is largely tied to immune state of the host and mode of acquisition. Infection with Fusarium species is primarily through the inhalation of airborne conidia, which subsequently germinate in the lungs and disseminate via the circulatory system, or through traumatic implantation with spore laden botanical material. A few cases reporting Fusarium infections after using contaminated contact lens solution and peritoneal dialysis have been described.1-3

Cases of disseminated infections occur most commonly in severely immunocompromised patients, such as those with acute leukemia, hematopoietic stem cell transplant, and prolonged neutropenia. These patients often present with rapidly progressive infections that are uniformly lethal without restoration of their neutrophil count.4,7 In a retrospective review of 44 cases of Fusarium infection at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC), the authors found that acute leukemia/myelodysplastic syndrome, hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT), neutropenia (ANC <1000 cells/µL), and lymphopenia (ALC <1000 cells/µL) were some of the most common characteristics among the patients who developed invasive fusariosis.4 In addition to fungemia, other common clinical manifestations of Fusarium infection in the MDACC case series included pulmonary disease and dissemination with skin lesions.4

Culture from blood and tissue are the two most common ways of diagnosing this infection. The appearance of the hyphae on histopathology will reveal septations and both acute and right-angle branching, which stain well with Gomori methanamine silver.1 Unlike other common molds, such as Aspergillus, patients with disseminated fusariosis are more likely to have positive blood cultures and skin lesions.1,4,7 In a high-risk patient with a mold infection, a positive 1,3-?-d-glucan in combination with a negative galactomannan test is suggestive of fusariosis.1 Fusarium pulmonary infection is detected more frequently on computed tomography compared to standard chest radiograph.5 Interestingly, in the MDACC series, none of the pulmonary disease had “halo sign” on chest imaging.4

Because of its rarity, no prospective clinical trials have been conducted on Fusarium and, thus, optimal treatment has not been established.1 Lipid formulations of amphotericin B (Liposomal amphotericin B [AmBisome®], amphotericin B lipid complex [Abelcet®]), and new triazoles (voriconazole, posaconazole) have shown some in vitro activity in animal models against Fusarium species.4,6 A few case reports have been published describing the use of combination antifungals in fusariosis, but evidence remains anecdotal.1,4,6 The MDACC case series demonstrated that prognosis and response to treatment is closely linked to the host’s immunity, and neutrophil recover is a protective factor.4,7 Without immune reconstitution, Fusarium remains a severe opportunistic infection of immunosuppressed patients with an extremely poor prognosis.

Key References:

- Nucci M, Anaissie E. “Fusarium infections in immunocompromised patients.” Clin Microbiol Rev 2006;20(4): 695-704

- Chang DC, Grant, GB, O’Donnell, K, et. al. Multistate outbreak of Fusarium keratitis associated with use of a contact lens solution. JAMA 2006;296:953–9633.

- Flynn JT, Meislich, D, Kaiser, BA, et. al. Fusarium peritonitis in a child on peritoneal dialysis: case report and review of the literature. Perit. Dial. Int. 1996;16:52–574.

- Campo M, Lewis RE, Kontoyiannis DP. Invasive fusariosis in patients with hematologic malignancies at a cancer center: 1998-2009. The Journal of Infection 2010;60:331-75.

- Marom EM, Holmes AM, Bruzzi JF, Truong MT, O’Sullivan PJ, Kontoyiannis DP. Imaging of pulmonary fusariosis in patients with hematologic malignancies. AJR American Journal of Roentgenology 2008;190:1605-96.

- Lamoth F, Kontoyiannis DP. Therapeutic challenges of non-Aspergillus invasive mold infections in immunosuppressed patients. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2019

- Kontoyiannis DP, Bodey GP, Hanna H, et al. Outcome determinants of fusariosis in a tertiary care cancer center: the impact of neutrophil recovery. Leukemia & Lymphoma 2004;45(1):139-41

Images and Figures: Image 1: Skin Lesion; Image 2: Chest CT; Image 3: Gram Stain; Image 4: High magnification Gram Stain- Fusarium