Title: Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage in an Immunocompromised Patient

Submitted by: Ian J. Kidder, MD; Seema Sethi, MD; Kathleen A. Linder, MD

Institution: Charles S. Kettles VA Medical Center, Ann Arbor, MI, USA

Email: kidderia@med.umich.edu

Date Submitted: May 29, 2024

History:

A 71-year-old man with a history of sarcoidosis complicated by multisystem involvement (liver, spleen, lung, brain, and lymph nodes), who had been maintained on prednisone (10 mg daily) and adalimumab, presented to our medical facility in late fall with a 3-month (m) history of progressive fatigue and weight loss.

The patient’s sarcoidosis was originally diagnosed about 15 years prior to admission, when Computed tomography (CT) imaging of the lungs showed bilateral hilar adenopathy and calcified splenic granulomas. He was treated with steroids and did well until 10 years later, when a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study of the brain revealed multiple lesions. A subsequent positron emission tomography (PET) CT revealed multiple liver and splenic lesions with hilar lymphadenopathy, all of which were PET-avid. Biopsy of a liver lesion demonstrated necrotizing granulomas; additional workup with TB-QuantiFERON and acid-fast stains of the sputum was unremarkable. He was treated with mycophenolate and did well until 1 year later until surveillance PET CT again showed multiple PET-avid lesions; repeat biopsy again revealed necrotizing granulomas. He was treated thereafter with prednisone and adalimumab. One month prior to admission, the patient was hospitalized for hypotension and anemia. He required a blood transfusion; esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed no evidence of active GI bleeding.

As forestated, the patient was admitted to the hospital after reporting a 3 m history of fatigue, odynophagia, lack of appetite, and a 30-pound weight loss; he reported symptoms were similar to prior sarcoidosis flares. CT revealed a 6 cm opacity in the left lung upper lobe with innumerable <6mm bilateral pulmonary opacities, mesenteric lymphadenopathy, and splenomegaly with multiple splenic lesions. Pulmonary was consulted and performed bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL); no microorganisms were present on Grocott’s methenamine silver or acid-fast stains.

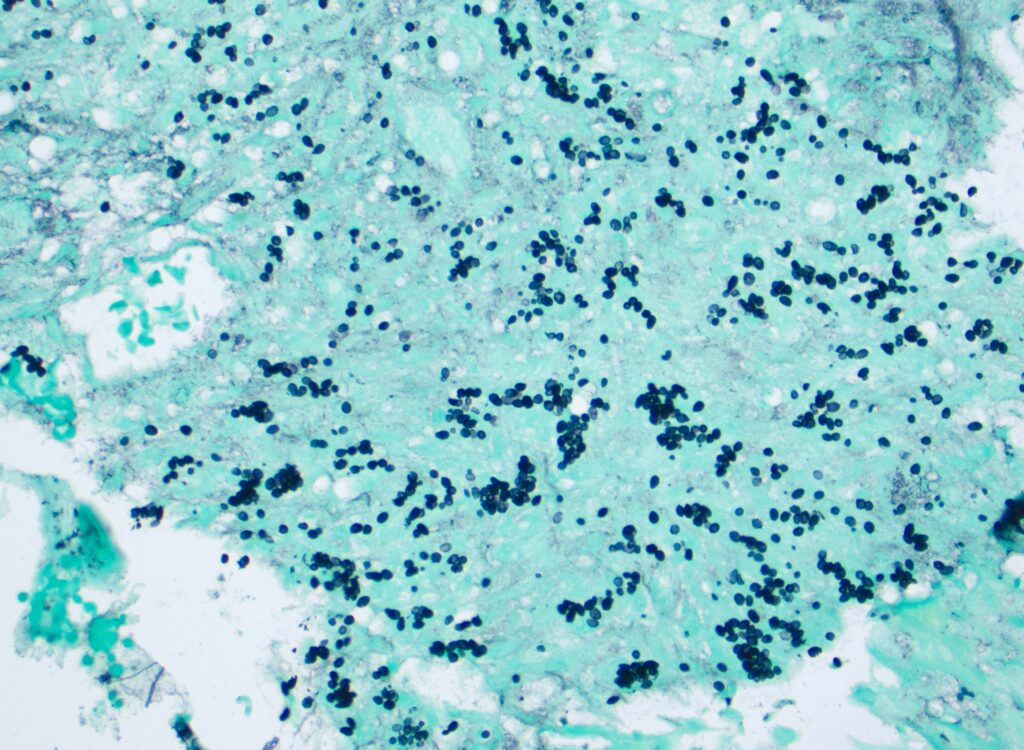

A few days after admission, the patient developed a fever (up to 39.3C) and tachycardia with hematochezia. A CT angiogram revealed an active arterial bleed in the proximal ileum. Interventional radiology successfully performed embolization of 3 terminal ileal branches off the superior mesenteric artery. The patient continued to have decreasing hemoglobin with recurrent hematochezia; upper endoscopy demonstrated a non-bleeding jejunal ulcer with clean base. Biopsies were taken (Figure 1).

Given patient’s immunocompromise and concern for a possible infectious etiology for pulmonary findings, infectious disease was consulted for further workup recommendations prior to initiation of additional immunosuppression.

Physical Examination:

- Vital signs: Temperature 37.6oC, BP: 99/62 mmHg, HR: 51, RR: 20, SpO2: 98%

- General: Tired-appearing man.

- HEENT: No JVD, moist mucous membranes, erythematous oropharynx with visible ulcerations.

- Cardiac: Normal rate and regular rhythm. No murmur.

- Pulmonary: Regular, non-labored breathing. Diminished airflow in the left upper lung field.

- Abdominal: Soft, non-tender, and non-distended.

- Neurological: Alert and oriented x3. Global extremity weakness (lower extremities more so than upper extremities).

- Skin: No rashes or jaundice.

- Extremities: No lower extremity edema

- Rectal exam: Small amount of maroon liquid in the rectal vault with brown stool.

Laboratory Examination:

- Sodium: 135

- Potassium: 4.4

- Chloride: 105

- Bicarbonate: 24

- Urea nitrogen: 27

- Creatinine: 0.85

- Albumin: 2.4

- Alkaline phosphatase: 93

- AST: 39

- ALT: 35

- Total bilirubin: 0.5

- White blood cell count: 3.35

- Hemoglobin: 9.1

- Hematocrit: 29.0

- Platelet count: 203

Question 1: What are probable/possible diagnoses?

Differential diagnosis:

- Sarcoidosis flare

- Tuberculosis with gastrointestinal involvement

- Disseminated endemic mycosis (histoplasmosis, blastomycosis)

- Duodenal or gastric ulcer

- Malignancy

Microbiology/Diagnostic Tests Performed:

- Histoplasma serum antigen: 17.60 ng/mL

- Histoplasma urine antigen: 13.07 ng/mL

- Blastomyces serum antigen: 10.67 ng/mL

- Blastomyces urine antigen: 4.87 ng/mL

- Beta-D-glucan: <31 pg/mL

- Galactomannan: index 0.18

- Blood aerobic/anaerobic cultures: No growth

- Blood fungal cultures: No growth

- AFB sputum cultures: No growth

- Bronchoalveolar lavage cultures: No growth (including fungal and AFB)

- Bronchoalveolar PJP and Legionella PCR: Negative

- Jejunal ulcer biopsy: Special stains for fungal microorganisms (PAS-D and GMS stains) demonstrate fungal organisms, consistent with Histoplasma (Figure 1)

Final Diagnosis: Disseminated Histoplasma capsulatum infection

Question 2: What treatment is recommended in the care of this patient?

After the H. capsulatum antigen testing returned, the patient was started on intravenous (IV) liposomal amphotericin B (initially 3 mg/kg/d); he was subsequently transitioned to posaconazole, with plans to continue this indefinitely given continued need for TNF-α inhibitor therapy.

This patient’s course was complicated by hypotension and an enlarging brain mass in the L temporal lobe. There was concern for CNS histoplasmosis and IV liposomal amphotericin B was started at 5 mg/kg/d. A lumbar puncture demonstrated elevated protein and positive Histoplasma serologies (positive M band); CSF cultures were negative. The patient remained on the higher dose of amphotericin B for 6 weeks before transitioning to voriconazole. MRI showed interval improvement in peripheral enhancement of the lesion.

About 1m after discharge, the patient had a bowel perforation and required bowel resection and colostomy formation. Anatomic pathology from surgical specimens identified ischemic bowel; no fungal elements were present.

Discussion:

Histoplasmosis is caused by Histoplasma capsulatum var. capsulatum, a dimorphic fungus that is found around the world. H. capsulatum is a saprophyte often found in soil containing large amounts of bird or bat droppings.1,2 Infection occurs via inhalation of Histoplasma microconidia; the organism is phagocytosed by macrophages and are disseminated throughout the reticuloendothelial system.3 Seroprevalence has been reported to be as high as a third of the general population in Central and South America.4 In the United States, H. capsulatum is primarily found in the Mississippi and Ohio River Valleys with positive skin testing seen in up to 80% of young adults.5,6

Most persons exposed to H. capsulatum remain asymptomatic or have self-limited symptoms.7 Since the lungs are the primary portal of entry, pulmonary histoplasmosis is the predominant form of symptomatic infection. Symptoms of pulmonary histoplasmosis may include fevers, dyspnea, dry cough, and pleuritic chest pain.8 Up to 10% of people exposed to H. capsulatum will develop acute symptomatic pulmonary histoplasmosis. Disseminated histoplasmosis typically occurs in immunocompromised patients, including patients with HIV with low CD4 counts and in patients on TNF-α inhibitors. Disseminated histoplasmosis often presents with fevers and nonspecific systemic symptoms like fatigue and weight loss.9 Laboratory findings often include pancytopenia, marked elevation in LDH, and transaminase elevations. 10,11,12.

The patient described in this vignette had gastrointestinal disease due to disseminated Histoplasma infection. GI histoplasmosis is most well described in patients with HIV disease, although a recent review stated 55% of North American patients with disseminated histoplasmosis had GI manifestations.14 However, only up to 11.8% of patients report GI symptoms,which are typically non-specific (abdominal pain, weight loss, and diarrhea).15 Gastrointestinal disease due to disseminated Histoplasma infection may be an underrecognized entity.

Gastrointestinal involvement of histoplasmosis can occur anywhere along the GI tract, although the ileocecal area is the most common, presumably due to abundant associated lymphoid tissue (Peyer patches).16 Hepatomegaly and splenomegaly are also common findings.17 CT imaging may reveal dilated or thickened bowel, as well as intraabdominal lymphadenopathy in up to two-thirds of patients.18 Of patients with intestinal involvement, signs can include gastrointestinal hemorrhage and bowel perforation. Small bowel involvement often is characterized by segmental inflammation and ulceration.12

IDSA recommendations for treatment of severe disseminated histoplasmosis include 1-2 weeks of IV amphotericin B (3mg/kg/d) followed by at least 12 months of oral itraconazole (200 mg 3 times daily for 3 days, then 200 mg twice daily). For immunosuppressed patients, lifelong suppressive therapy with itraconazole may be indicated.19 If patients cannot tolerate itraconazole, posaconazole and voriconazole are considered reasonable alternatives, although head-to-head data are not available for newer azoles.20

This case highlights the importance of considering histoplasmosis as a source of gastrointestinal hemorrhage, particularly in patients who are at risk for disseminated histoplasmosis. GI involvement from H. capsulatum can occur anywhere in the GI tract, although the area around the ileocecal valve is the most frequently affected. Gastrointestinal manifestations of histoplasmosis may be underrecognized.

Key References:

- EMMONS CW. Isolation of Histoplasma capsulatum from soil. Public Health Rep (1896). 1949 Jul 15;64(28):892-6. PMID: 18134389.

- CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/histoplasmosis/definition.html

- CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/histoplasmosis/causes.html

- Adenis AA, Valdes A, Cropet C, McCotter OZ, Derado G, Couppie P, Chiller T, Nacher M. Burden of HIV-associated histoplasmosis compared with tuberculosis in Latin America: a modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018 Oct;18(10):1150-1159. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30354-2. Epub 2018 Aug 23. PMID: 30146320; PMCID: PMC6746313.

- MANOS NE, FEREBEE SH, KERSCHBAUM WF. Geographic variation in the prevalence of histoplasmin sensitivity. Dis Chest. 1956 Jun;29(6):649-68. doi: 10.1378/chest.29.6.649. PMID: 13317782.

- Edwards LB, Acquaviva FA, Livesay VT, Cross FW, Palmer CE. An atlas of sensitivity to tuberculin, PPD-B, and histoplasmin in the United States. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1969 Apr;99(4):Suppl:1-132. PMID: 5767603.

- CDC. Histoplasmosis | CDC Yellow Book 2024

- Azar MM, Malo J, Hage CA. Endemic Fungi Presenting as Community-Acquired Pneumonia: A Review. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2020 Aug;41(4):522-537. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1702194. Epub 2020 Jul 6. PMID: 32629490.

- Araúz AB, Papineni P. Histoplasmosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2021 Jun;35(2):471-491. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2021.03.011. PMID: 34016287.

- Arunkumar P, Crook T, Ballard J. Disseminated histoplasmosis presenting as pancytopenia in a methotrexate-treated patient. Am J Hematol. 2004 Sep;77(1):86-7. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20058. PMID: 15307113.

- Corcoran GR, Al-Abdely H, Flanders CD, Geimer J, Patterson TF. Markedly elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase levels are a clue to the diagnosis of disseminated histoplasmosis in patients with AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 1997 May;24(5):942-4. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.5.942. PMID: 9142797.

- Muhanna A, Nimri FM, Almomani ZA, Al Momani L, Likhitsup A. Granulomatous Hepatitis Secondary to Histoplasmosis in an Immunocompetent Patient. Cureus. 2021 Sep 1;13(9):e17631. doi: 10.7759/cureus.17631. PMID: 34513533; PMCID: PMC8409462.

- Kahi CJ, Wheat LJ, Allen SD, Sarosi GA. Gastrointestinal histoplasmosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005 Jan;100(1):220-31. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40823.x. PMID: 15654803.

- Ekeng BE, Itam-Eyo AE, Osaigbovo II, Warris A, Oladele RO, Bongomin F, Denning DW. Gastrointestinal Histoplasmosis: A Descriptive Review, 2001-2021. Life (Basel). 2023 Mar 3;13(3):689. doi: 10.3390/life13030689. PMID: 36983844; PMCID: PMC10051669.

- Wheat LJ, Connolly-Stringfield PA, Baker RL, Curfman MF, Eads ME, Israel KS, Norris SA, Webb DH, Zeckel ML. Disseminated histoplasmosis in the acquired immune deficiency syndrome: clinical findings, diagnosis and treatment, and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1990 Nov;69(6):361-74. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199011000-00004. PMID: 2233233.

- Cappell MS, Mandell W, Grimes MM, Neu HC. Gastrointestinal histoplasmosis. Dig Dis Sci. 1988 Mar;33(3):353-60. doi: 10.1007/BF01535762. PMID: 3277825.

- Goodwin RA Jr, Shapiro JL, Thurman GH, Thurman SS, Des Prez RM. Disseminated histoplasmosis: clinical and pathologic correlations. Medicine (Baltimore). 1980 Jan;59(1):1-33. PMID: 7356773.

- Suh KN, Anekthananon T, Mariuz PR. Gastrointestinal histoplasmosis in patients with AIDS: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 2001 Feb 1;32(3):483-91. doi: 10.1086/318485. Epub 2001 Jan 30. PMID: 11170958.

- Wheat LJ, Freifeld AG, Kleiman MB, Baddley JW, McKinsey DS, Loyd JE, Kauffman CA; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2007 Oct 1;45(7):807-25. doi: 10.1086/521259. Epub 2007 Aug 27. PMID: 17806045.

- Panel on Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, HIV Medicine Association, and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Available at https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/adult-andadolescent-opportunistic-infection.

Images and Figures:

Figure 1. Small, uniform, oval, narrow based budding yeasts, 1-5 micrometer in diameter, highlighted on special stain for fungal microorganisms (GMS stain).