Title: Cerebral Phaeohyphomycosis due to Curvularia sps.

Submitted by: Monica George, Audrey Wanger, Luis Ostrosky and Ana Salas

Institution: University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston

Email: mgeorgepalop@uth.tmc.edu

Date Submitted: 07/13/2022

History:

A 39-year-old female with a past medical history of HTN, morbid obesity, chronic rhinosinusitis, s/p bilateral functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS) 8 months ago, presented with a 2-month history of worsening frontal headaches, accentuated by standing position and were accompanied by altered sense of smell and nausea.

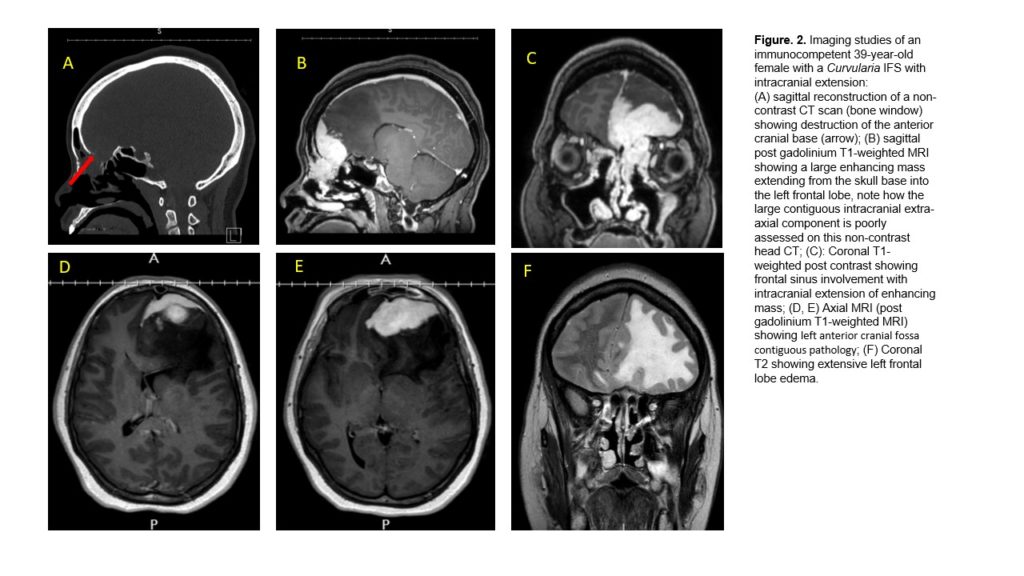

Admission CT scan head revealed left frontal lobe cerebral edema extending from the cribriform plate to the corpus callosum. The patient was admitted for further diagnostic workup and treatment.

Physical Examination:

T: 98.2 °F (Oral) HR:100 bpm, RR: 18, BP: 158/88, SpO2:97% Wt: 141 Kg, BMI: 47.41 kg/m2

GENERAL: awake, active, well-developed, obese

HEAD: Normocephalic, atraumatic

EYES – PERRLA, clear conjunctiva. Left eye proptosis

NOSE: Nasal endoscopy: Left-sided mucosal mass obscuring a significant portion of L nasal airway. The mucosa lining of the inferior and middle turbinates is covered with crusting

PHARYNX: Mouth pink, MMM. No tonsillar enlargement, exudate, or erythema

EARS: External ear clear w/o drainage b/l, inner ear canal noninflamed

NECK: Supple, thyroid nonpalpable, full ROM, no significant adenopathy

HEART: Regular rhythm. No murmurs or gallops

SKIN: Warm, dry, and well perfused. Good turgor. No lesions, nodules or rashes are noted

LUNGS: Clear to auscultation bilaterally. No wheezing. Normal respiratory sounds

NEUROLOGIC: Vision remains intact without decreased acuity. No focal sensory or motor deficits noted. CN II – XII are intact. DTRs intact. Sluggish thought processPSYCHIATRIC: Appropriate mood and affect

Laboratory Examination:

WBC: 14,000 cells/mL, Hb: 7.6 g/dL, Plt: 232 K cells/mL, Eosinophils 4.9% Creatinine 0.9 mg/dL, ESR 55, CRP 11.

Radiology:

- CT Sinuses without contrast:

1. Sinuses: left anterior skull base and left anterior cranial fossa contiguous pathology with a differential diagnosis that includes sinus-nasal pathology with intracranial extension (including granulomatous invasive fungal sinusitis) and intracranial pathology with sinus-nasal extension (including meningioma/solitary fibrous tumor). The lesion has associated osseous dehiscence within portions of the left frontal sinus, left medial orbital wall, left ethmoid sinus, and left cribriform plate. The CT exam exhibits erosion of the left lamina papyracea and ethmoid sinus walls in the region of the nasolacrimal duct. There is no frank invasion of the orbit but there is a mass effect on the left extraconal fat displacement of the extraocular muscles laterally.

2. ?Limited assessment of the large intracranial component.

- MRI Brain w/wo contrast: A homogeneously enhancing solid extra-axial mass in the left anterior cranial fossa with extension to involve the left superior nasal vault and portions of the right anterior cranial fossa just across the midline. The mass is invading the left nasoethmoidal region, but there is no frank invasion of the orbit at this time. Primary differential diagnosis would include meningioma, esthesioneuroblastoma, and solitary fibrous tumor.

Question 1: What are probable/possible diagnoses?

Our patient had a history of nasal polyposis and chronic rhinosinusitis. Fungal etiology should always be suspected when there is a history of chronic sinusitis that does not improve with prolonged courses of antibiotics and there is evidence of invasive infection.

Fungal rhinosinusitis is classified into Allergic Fungal Rhinosinusitis (AFRS) and Invasive Fungal Sinusitis (IFS) [1]. It is of crucial importance to distinguish between the two entities, as IFS is potentially lethal. Histopathology of IFS shows fungal invasion into the mucosa accompanied by tissue necrosis and associated chronic inflammatory infiltrates along with granulomas and giant cells. Acute IFS occurs in diabetic, immunocompromised hosts and is usually due to Aspergillus species, Fusarium species, and the Mucorales. Chronic IFS can be frequently seen in immunocompetent hosts and is most commonly caused by dematiaceous molds, such as Bipolaris, Curvularia, and Alternaria spp. Less frequently it can also be caused by Aspergillus spp and other hyaline molds, such as Scedosporium apiospermum complex [2, 3, 4, 5].

The extension of the Dematiaceous fungal infections into the CNS is known as Cerebral Phaeohyphomycosis, and it has been shown that it affects immunocompetent as well as immunocompromised individuals [6].

In our case, the histopathology of the surgical specimen revealed the presence of fungal hyphae in the sinus mucosa and the associated granulomas suggesting chronic IFS. CT scan of sinuses during this admission revealed radiological findings consistent with an invasive process eroding the skull base bones, and the medial wall of the left orbit consistent with IFS. MRI of the Brain showed findings consistent with intracranial extension of the infection. In this clinical scenario, we had a case of possible cerebral phaeohyphomycosis. Our differential diagnosis included Bipolaris, Curvularia, Alternaria, and Aspergillus sps as the most likely etiologic microorganisms.

Microbiology/Diagnostic Tests Performed:

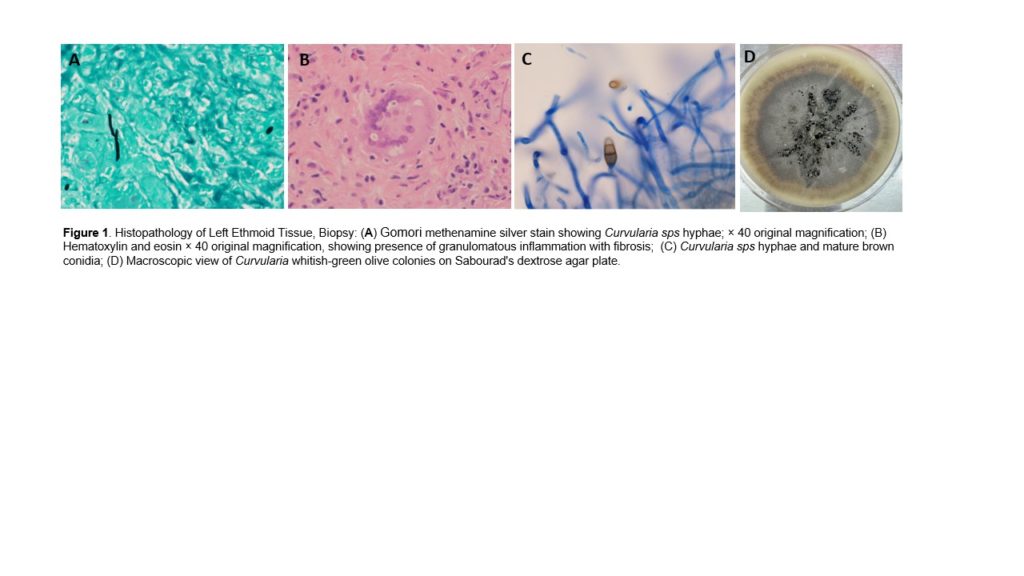

- Anatomic Pathology of Sinus mucosa biopsy showed granulomatous inflammation + fibrosis, GMS was positive for fungal elements with hyphae and yeast forms.

- Culture of Sinus mucosa tissue (biopsy): Positive for MRSA + Citrobacter koseri + Curvularia sps.

- Curvularia sps Susceptibility panel

Posaconazole 0.06 mcg/ml No Established Breakpoints

Voriconazole 2 mcg/ml No Established Breakpoints

Isavuconazole 8 mcg/ml No Established Breakpoints

Final Diagnosis:

Invasive Fungal Sinusitis due to Curvularia sps with CNS extension: Cerebral Phaeohyphomycosis

Question 2: What treatment is recommended in the care of this patient?

Question 1: What are probable/possible diagnoses?

Our patient had a history of nasal polyposis and chronic rhinosinusitis. Fungal etiology should always be suspected when there is a history of chronic sinusitis that does not improve with prolonged courses of antibiotics and there is evidence of invasive infection.

Fungal rhinosinusitis is classified into Allergic Fungal Rhinosinusitis (AFRS) and Invasive Fungal Sinusitis (IFS) [1]. It is of crucial importance to distinguish between the two entities, as IFS is potentially lethal. Histopathology of IFS shows fungal invasion into the mucosa accompanied by tissue necrosis and associated chronic inflammatory infiltrates along with granulomas and giant cells. Acute IFS occurs in diabetic, immunocompromised hosts and is usually due to Aspergillus species, Fusarium species, and the Mucorales. Chronic IFS can be frequently seen in immunocompetent hosts and is most commonly caused by dematiaceous molds, such as Bipolaris, Curvularia, and Alternaria spp. Less frequently it can also be caused by Aspergillus spp and other hyaline molds, such as Scedosporium apiospermum complex [2, 3, 4, 5].

The extension of the Dematiaceous fungal infections into the CNS is known as Cerebral Phaeohyphomycosis, and it has been shown that it affects immunocompetent as well as immunocompromised individuals [6].

In our case, the histopathology of the surgical specimen revealed the presence of fungal hyphae in the sinus mucosa and the associated granulomas suggesting chronic IFS. CT scan of sinuses during this admission revealed radiological findings consistent with an invasive process eroding the skull base bones, and the medial wall of the left orbit consistent with IFS. MRI of the Brain showed findings consistent with intracranial extension of the infection. In this clinical scenario, we had a case of possible cerebral phaeohyphomycosis. Our differential diagnosis included Bipolaris, Curvularia, Alternaria, and Aspergillus sps as the most likely etiologic microorganisms.

Microbiology/Diagnostic Tests Performed:

- Anatomic Pathology of Sinus mucosa biopsy showed granulomatous inflammation + fibrosis, GMS was positive for fungal elements with hyphae and yeast forms.

- Culture of Sinus mucosa tissue (biopsy): Positive for MRSA + Citrobacter koseri + Curvularia sps.

- Curvularia sps Susceptibility panel

Posaconazole 0.06 mcg/ml No Established Breakpoints

Voriconazole 2 mcg/ml No Established Breakpoints

Isavuconazole 8 mcg/ml No Established Breakpoints

Final Diagnosis:

Invasive Fungal Sinusitis due to Curvularia sps with CNS extension: Cerebral Phaeohyphomycosis

Question 2: What treatment is recommended in the care of this patient?

Treatment:

Treatment of IFS requires aggressive surgical debridement and systemic antifungal drugs. Prognosis tends to be poor as the infection is often difficult to control.

On admission, the patient underwent navigation-assisted left endoscopic ethmoidectomy, frontal sinusotomy, and sphenoidotomy. She was also evaluated by neurosurgery and was deemed of no acute neurosurgery intervention required. In addition, the patient was started on Keppra and dexamethasone for seizures prophylaxis and cerebral edema.

Our patient was initially treated with AmBisome for granulomatous inflammation with fibrosis and fungal elements seen on left ethmoid sinus biopsy consistent with IFS (invasive fungal sinusitis). She was also placed on vancomycin + ceftriaxone for sinus culture positive for MRSA and Citrobacter koseri. The patient then developed AKI (Cr. 2.36 mg/dL, baseline 0.9, eGFR: 25 mL/min/1.73m2) with concerns for ATN therefore, AmBisome and vancomycin were subsequently discontinued and switched to posaconazole and linezolid, ceftriaxone continued. After 1 week of treatment, the patient was discharged on linezolid 600 mg PO q12h and posaconazole 300 mg PO bedtime x 90 days + ceftriaxone 2gr IV q12h to complete 2 weeks of treatment.

Outcome: The patient was seen at outpatient follow-up 2 weeks after discharge, she reported resolution of headaches, but still with some generalized weakness, brain images will be repeated in 2 months.

Discussion:

Cerebral phaeohyphomycosis is caused by dematiaceous mold, these fungi are unique due to the presence of melanin in their cell walls, which has been proposed as a virulence factor of all dematiaceous fungi [1]. In the CNS, melanin acts as a shield to the fungi protecting them from free radicals produced by the microglial cells. Another interesting property of melanin is that it seems to confer this group of fungi their ability to spread through neurons [7].

In a review of 101 cases of CNS phaeohyphomycosis, 73% were fatal, even though most of the patients were immunocompetent without underlying risk factors [2]. Other case reports suggest exceptionally high mortality rates due to dematiaceous fungi regardless of affecting immunocompetent or immunocompromised patients as opposed to fungal infections of the CNS caused by Aspergillus or Mucor, which have better outcomes in immunocompetent patients [6, 7, 8]. In the International Case Registry for probable/proven phaeohyphomycosis created by the MSG (Mycoses Study Group) it is shown that local deep infections were caused by 16 different genera, although only 3 (Alternaria, Curvularia, Lomentospora) were responsible for over half of these cases (53%) [9].

Here, we present a case of Curvularia IFS with intracranial extension: Cerebral Phaeohyphomycosis. Our patient underwent initial sinus surgery due to chronic sinusitis 8 months before and the initial pathology revealed features consistent with IFS. However, at that time, imaging did not show any evidence of intracranial extension. She later presented with severe worsening headaches and proptosis, and repeat imaging showed extension of the fungal infection from the ethmoid sinus into the orbit, a common presentation of the IFS with intracranial extension known as the orbital apex syndrome.[10], resulting in the mild proptosis seen in our patient. We hypothesize that the fungus found its way to the CNS in part favored by the post-surgical normal disruption of the sinonasal anatomical natural barrier through the ethmoidal cells and cribriform plate, invading the anterior fossa. These changes would have offered an opportunity for the neurotropic nature of Curvularia, characteristic of all dematiaceous fungi, to further invade intracranially. In addition, the use of daily intranasal corticosteroids after the initial FESS, which is usually the treatment for allergic fungal sinusitis (AFS), could have created an even more favorable environment for the local invasion of the fungi in this distinct clinical entity, IFS.

Phaeohyphomycosis treatment requires both surgical resection and aggressive antifungal therapy. Complete surgical excision is associated with a higher rate of success as compared to aspiration which invariably results in recurrence [11,12,13]. Our patient underwent extensive surgical excision of the affected sinonasal affected mucosa with debridement of ethmoidal cells. As the patient was stable and neurologically intact a decision was made to initially treat with aggressive antifungal treatment before performing neurosurgical intervention to drain the intracranial extension of the abscess. At the time this case report is written, the patient headache was resolved at the first outpatient follow up, 2 weeks after discharge. We continue to follow for now.

The optimal therapy for these infections remains uncertain. Data from the literature linking treatment and outcomes are sparse, with outcomes generally not well documented. The guidelines suggest itraconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole as active drugs, with voriconazole, preferred for CNS infection and posaconazole utilized for salvage therapy [14]

Evidence-based guided therapy for phaeohyphomycosis relies on single case or case series reports as randomized clinical trials?are unlikely given the sporadic nature of the disease. It is very important to report successful and unsuccessful outcomes of a particular approach.

Key References:

- Wong EH, Revankar SG. Dematiaceous Molds. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016 Mar;30(1):165-78. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2015.10.007. PMID: 26897066.

- Ferguson BJ. Definitions of fungal rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2000; 33:227–35.

- Marinucci, Victoria et al. “Invasive Fungal Rhinosinusitis Caused by Curvularia in a Patient With Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: A Case Report.” Journal of pharmacy practice vol. 35,2 (2022): 311-316. doi:10.1177/0897190020966196

- Alarifi I., et al. Chronic granulomatous invasive fungal sinusitis: a case series and literature review. Ear Nose Throat J. 2021;100:720S–727S.

- El-Morsy, S M et al. “Allergic fungal rhinosinusitis: detection of fungal DNA in sinus aspirate using polymerase chain reaction.” The Journal of laryngology and otology vol. 124,2 (2010): 152-60. doi:10.1017/S0022215109991204

- Revankar, Sanjay G et al. “Primary central nervous system phaeohyphomycosis: a review of 101 cases.” Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America vol. 38,2 (2004): 206-16. doi:10.1086/380635

- Jacobson, Eric S. “Pathogenic roles for fungal melanins.” Clinical microbiology reviews 13.4 (2000): 708-717.

- Li, Dong Ming, and G Sybren de Hoog. “Cerebral phaeohyphomycosis–a cure at what lengths?.” The Lancet. Infectious diseases vol. 9,6 (2009): 376-83. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70131-8

- Revankar, Sanjay G et al. “A Mycoses Study Group International Prospective Study of Phaeohyphomycosis: An Analysis of 99 Proven/Probable Cases.” Open forum infectious diseases vol. 4,4 ofx200. 26 Sep. 2017, doi:10.1093/ofid/ofx200

- Dooley DP, Hollsten DA, Grimes SR, et al. Indolent orbital apex syndrome caused by occult mucormycosis. J Clin Neuroophthalmol 1992; 12: 245

- Carter, Elliot, and Carole Boudreaux. “Fatal cerebral phaeohyphomycosis due to Curvularia lunata in an immunocompetent patient.” Journal of clinical microbiology vol. 42,11 (2004): 5419-23. doi:10.1128/JCM.42.11.5419-5423.2004

- Smith, Tai et al. “Optic atrophy due to Curvularia lunata mucocoele.” Pituitary vol. 10,3 (2007): 295-7. doi:10.1007/s11102-007-0012-3

- Singh, Harminder et al. “Curvularia fungi presenting as a large cranial base meningioma: case report.” Neurosurgery vol. 63,1 (2008): E177; discussion E177. doi:10.1227/01.NEU.0000335086.77846.0A

- Chowdhary, A et al. “ESCMID and ECMM joint clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and management of systemic phaeohyphomycosis: diseases caused by black fungi.” Clinical microbiology and infection: the official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases vol. 20 Suppl 3 (2014): 47-75. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12515