Title: Daring to Hear: A Case of Fungal Skull Base Osteomyelitis

Submitted by: Kemar Barrett, M.B.B.S

Institution: Mayo Clinic, Rochester – Division of Public Health, Infectious Diseases and Occupational Medicine

Email: barrett.kemar@mayo.edu

Date Submitted: 08/20/2025

History:

A 57-year-old male presented to the emergency department with a 10-day history of left-sided facial weakness and pain. Symptoms began approximately two weeks after his return from a six-month stay in Florida. Associated features included facial asymmetry, impaired lip seal with difficulty drinking through a straw, and headache. He also reported a six-month history of intermittent left-sided otorrhea and otalgia. He denied nausea, vomiting, fever, chills, or visual disturbances.

His medical history was significant for type 2 diabetes mellitus complicated by nephropathy and retinopathy, end-stage renal disease on peritoneal dialysis, and seborrheic dermatitis.

Further inquiry revealed multiple emergency department and primary care visits over the past six months for recurrent left otalgia, otorrhea, ear fullness, decreased hearing, and nasal congestion. He was initially treated with oral amoxicillin–clavulanate and topical ciprofloxacin otic drops, with temporary improvement. Four months prior to presentation, he was evaluated by ENT, where examination showed an erythematous left external auditory canal with medial otorrhea and an edematous tympanic membrane containing a bullae. The bullae was marsupialized and suctioned, and he was prescribed a course of clotrimazole drops followed by alcohol/acetic acid drops. He was scheduled for follow-up but became lost to follow-up due to extended travel.

Physical Examination:

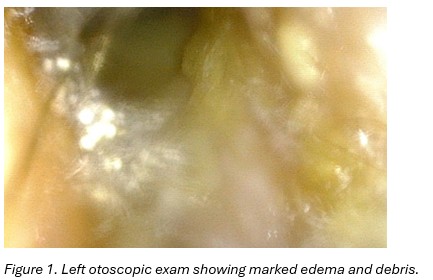

Examination of the left ear revealed significant medial purulence. The external auditory canal appeared thickened and erythematous, with no obvious perforation (Figure 1). There was no mastoid fluctuance, erythema, or tenderness. The tympanic membrane was not visible.

Neurological examination demonstrated decreased sensation to light touch in the left trigeminal nerve distribution (V1–V3) and marked weakness with asymmetry of the left side of the face, consistent with cranial nerve VII palsy.

Laboratory Examination:

Complete blood count showed hemoglobin 12 g/dL, white blood cell count 8.1 × 10⁹/L, and platelet count 289 × 10⁹/L. Inflammatory markers were elevated, with ESR 77 mm/hr (reference <22) and CRP 25.6 mg/L (reference <5.0). His hemoglobin A1c was 5.3%.

Question 1: What are probable/possible diagnoses?

Probable/possible diagnoses:

Skull base osteomyelitis, otitis externa without osteomyelitis, malignant lesion of the external ear canal or nasopharynx, cholesteatoma with or without secondary infection, granulomatous disease

Microbiology/Diagnostic Tests Performed:

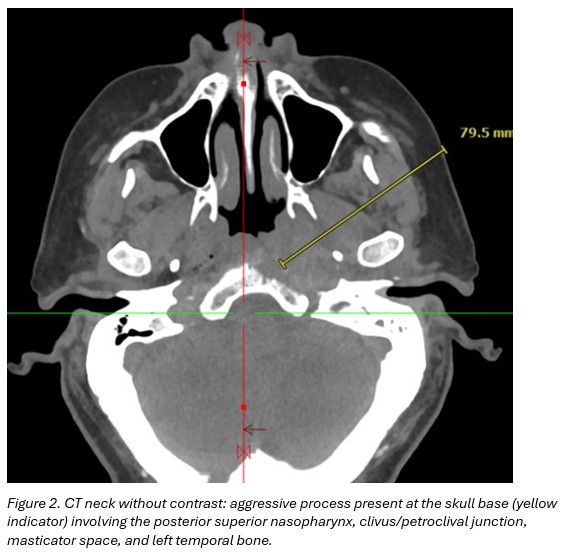

CT neck without contrast: aggressive process present at the skull base involving the posterior superior nasopharynx, clivus/petroclival junction, masticator space, and left temporal bone. (Figure 2)

HIV-1/-2 Ag and Ab: negative

Histoplasma/Blastomyces Ag and Ab: negative

Cryptococcus Antigen: negative

Serum (1,3) Beta-D-Glucan (Fungitell): 210 pg/mL (<60)

Serum Aspergillus Ag: 0.662 (<0.5)

CT guided biopsy

• Peri-clival fluid culture: Aspergillus flavus

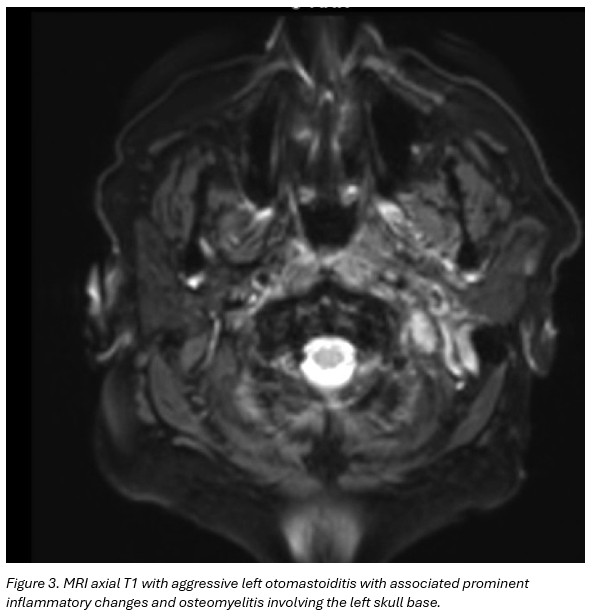

MRI brain and neck soft tissue with contrast: Findings suggestive of aggressive left otomastoiditis with associated prominent inflammatory changes and osteomyelitis involving the left skull base. No evidence for underlying neoplasm, or drainable fluid collection/abscess. No intracranial extension of disease. (Figure 3)

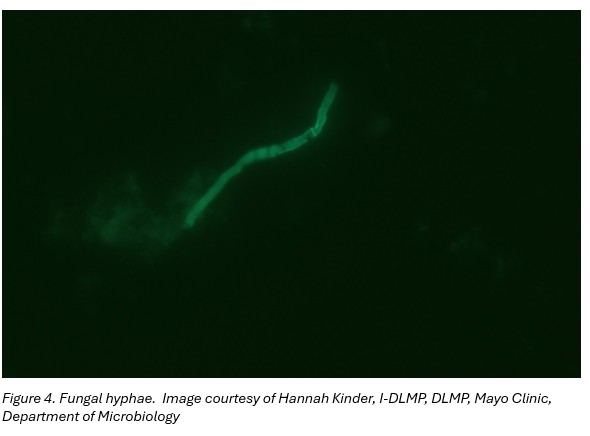

Left ear swab culture: hyphae suggestive of filamentous fungus (Figure 4) later identified as Aspergillus flavus

Bacterial cultures on left ear swab, bone and Peri-clival fluid: negative

Broad Range Bacteria PCR+Sequencing on bone and Peri-clival fluid: no bacterial DNA detected

CYP2C19 Phenotype: normal (extensive) metabolizer

Final Diagnosis: Necrotizing otitis externa with skull base osteomyelitis secondary to Aspergillus flavus

Question 2: What treatment is recommended in the care of this patient?

Treatment:

Following CT-guided biopsy, the patient was started on cefepime 2 g IV every 48 hours (dose adjusted for peritoneal dialysis) and voriconazole 400 mg orally every 12 hours for two doses, followed by 200 mg orally every 12 hours. Micafungin 100 mg IV daily was later added pending therapeutic assessment of voriconazole levels.

ENT deferred surgical intervention due to the patient’s multiple comorbidities and the absence of an abscess or drainable collection on MRI. Hyperbaric medicine was consulted as a potential adjunct to medical therapy; however, insurance did not approve coverage.

Voriconazole trough level, obtained five days after initiation, was supratherapeutic at 6.7 mcg/mL (reference range 1.0–5.5 mcg/mL). The regimen was subsequently adjusted to 200 mg orally each morning and 100 mg each evening. Micafungin was discontinued at that time.

Outcome:

At outpatient infectious diseases follow-up two weeks after discharge, the patient reported new-onset tremors and myoclonic jerks that interfered with daily activities, along with distressing visual hallucinations. His headache and rhinorrhea had resolved; however, residual cranial nerve VII deficits persisted.

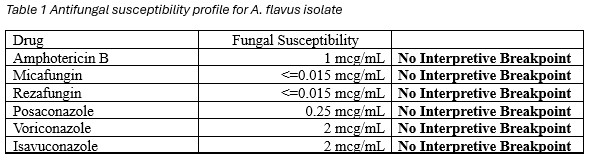

A repeat voriconazole trough level remained supratherapeutic at 6.1 mcg/mL (reference range 1.0–5.5 mcg/mL). After review of fungal susceptibilities (Table 1), voriconazole was discontinued and therapy was switched to posaconazole delayed-release, 300 mg once daily following a loading regimen of 300 mg twice daily for two doses on day one.

His tremors and myoclonus subsequently improved. He was planned for a tentative 3–6 month course of antifungal therapy, with duration guided by ongoing clinical and radiological reassessments.

Discussion: (500 words)

Skull base osteomyelitis (SBO) is a rare but life-threatening infection, most frequently arising as a complication of malignant otitis externa in elderly patients with diabetes mellitus or compromised immune systems. The condition is typically bacterial in origin, with Pseudomonas aeruginosa being the most common pathogen.1 Fungal SBO is considerably less common accounting for about 40% of patients in some cohorts. Aspergillus spp. are the most commonly implicated organism.2

Our patient demonstrated multiple classical risk factors for SBO, including poorly controlled type 2 diabetes complicated by nephropathy and retinopathy, and end-stage renal disease on peritoneal dialysis. His protracted course of recurrent otorrhea, otalgia, and progressive cranial neuropathies was consistent with indolent fungal invasion of the temporal bone and skull base. The presence of cranial nerve VII palsy and trigeminal sensory involvement further emphasized the extent of disease, as cranial neuropathies are hallmarks of advanced SBO and correlate with poor prognosis.3

Diagnosis of SBO can be challenging due to its insidious onset and overlap with chronic otitis externa or media. Imaging modalities such as MRI and CT are crucial to delineate bone involvement and exclude abscess formation, while biopsy remains the gold standard for definitive microbiological diagnosis.3,4 In this case, CT-guided biopsy facilitated targeted antifungal therapy, underscoring the importance of tissue sampling in suspected fungal SBO.

Medical management of fungal SBO requires prolonged systemic antifungal therapy, often for several months, and choice of agent should be guided by susceptibility testing. Voriconazole is considered first-line therapy for invasive aspergillosis due to its excellent tissue penetration and efficacy.5 However, therapeutic drug monitoring is essential, as supratherapeutic levels can result in neurotoxicity, including tremors, hallucinations, and myoclonus, as observed in our patient. Switching to posaconazole, which has a favorable side-effect profile and broad antifungal activity, led to clinical improvement. This highlights the importance of individualized antifungal selection, dose adjustment, and close monitoring in patients with renal impairment and polypharmacy.

Surgical intervention in SBO is typically reserved for cases with localized abscesses or sequestra, as debridement of skull base bone carries significant morbidity.3,6 In our case, ENT specialists deferred surgery given the absence of drainable collections and the patient’s substantial comorbidities. Adjunctive therapies such as hyperbaric oxygen have been proposed to enhance antimicrobial efficacy and bone healing, but it is not well established due to scarce literature.7

This case illustrates several key considerations in fungal SBO: the importance of high clinical suspicion in at-risk populations, the role of biopsy and imaging in establishing diagnosis, the need for prolonged antifungal therapy with careful therapeutic monitoring, and the challenges posed by comorbidities that limit surgical and adjunctive options. Early recognition and tailored management remain critical to improving outcomes in this rare but devastating disease. Prospective studies are needed to better understand the optimal approach to the diagnosis and management and to improve clinical outcomes.

Key References:

- Nadol, J. B. (1980). Histopathology of pseudomonas osteomyelitis of the temporal bone starting as malignant external otitis. American Journal of Otolaryngology, 1(5), 359–371.

- Chapman, P., Choudhary, G., & Singhal, A. (2021). Skull base osteomyelitis: A Comprehensive Imaging review. American Journal of Neuroradiology, 42(3), 404–413.

- Hamiter, M., Amorosa, V., Belden, K., Gidley, P. W., Mohan, S., Perry, B., & Kim, A. H. (2023). Skull base osteomyelitis. Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America, 56(5), 987–1001.

- Erdman, W. A., Tamburro, F., Jayson, H. T., Weatherall, P. T., Ferry, K. B., & Peshock, R. M. (1991). Osteomyelitis: characteristics and pitfalls of diagnosis with MR imaging. Radiology, 180(2), 533–539.

- Patterson, T. F., Thompson, G. R., Denning, D. W., Fishman, J. A., et al (2016). Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Aspergillosis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 63(4), e1–e60.

- Go, B. C., Wong, K., Eliades, S. J., Brant, J. A., Bigelow, D. C., Ruckenstein, M. J., & Hwa, T. P. (2024). Reassessing the utility of surgical intervention for skull base osteomyelitis: A 16‐Year experience. Otolaryngology, 171(1), 197–204.

- Sandner, A., Henze, D., Neumann, K., & Kösling, S. (2009). Nutzen der HBO bei der Therapie der fortgeschrittenen Schädelbasisosteomyelitis. Laryngo-Rhino-Otologie, 88(10), 641–646.