Title: A Rare Case of Fungal Empyema due to Saccharomyces cerevisiae

Submitted By: Michael Temple MD1, Zoheb Irshad Sulaiman DO2, Caroline A. Hamilton PA-C, MPH2, Jose A. Vazquez MD2

Institution:

1Medical College of Georgia, Wellstar MCG Health, Internal Medicine Residency Program

2Medical College of Georgia, Wellstar MCG Health, Division of Infectious Diseases

Email: mtemple@augusta.edu

Date Submitted: 6/27/2024

Case Report:

A 69-year-old man with a history of stage IIIB esophageal adenocarcinoma status post chemoradiation presented with a hydropneumothorax complicated by a polymicrobial multidrug resistant empyema. One month prior, he underwent surgical resection with Ivor Lewis esophagectomy, jejunostomy tube placement, and pyloromyotomy with the thoracic surgery service. Post-op he developed a loculated right pleural effusion after an esophageal perforation. This required a right sided video assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) and esophageal stenting. During the prior admission he received prolonged broad spectrum antimicrobial therapy and was discharged on fluconazole and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid for four weeks. During this hospitalization he was admitted to the ICU and intubated for respiratory failure. A right thoracostomy tube was inserted to address his pneumothorax. Purulent pleural fluid was drained and sent for gram stain and cultures.

His pleural fluid cultures grew KPC-producing Enterococcus cloacae, Klebsiella pneumoniae, vancomycin resistant Enterococcus faecium (VRE), Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and Lactobacillus fermentum. Infectious diseases (ID) service was consulted for antibiotic recommendations and management of his polymicrobial empyema. He was transitioned to Ceftazidime-Avibactam to target KPC E. cloacae, vancomycin was switched to linezolid to treat VRE, and micafungin was switched to fluconazole to cover S. cerevisiae.

Vitals & Measurements:

T: 36.9 °C; HR: 75/min; RR: 21/min; BP: 100/64 mmHg; SpO2: 100% on 4 L/min nasal cannula

Physical Exam:

General: Awake, resting comfortably in no acute distress

HEENT: Sclera anicteric.

Cardiovascular: Regular rate and rhythm, no murmurs, rubs, or gallops appreciated.

Respiratory: Right sided chest tube to suction with serosanguineous drainage.

Gastrointestinal: Soft, non-distended, non-tender

Integumentary: Abdominal incision with staples in place with staples without erythema or tenderness. Jejunal site without erythema.

Neurologic: No gross neurologic deficits

Laboratory Examination:

White blood cell (WBC): 8,200/mm3

Hemoglobin (Hgb): 7.9 g/dL

Hematocrit (Hct): 23.7 %

Platelet Count: 199,000/mm3

Segs: 97%

Band: 16%

Creatinine: 0.65 mg/dL

Glucose: 200 mg/dL

The presence of Saccharomyces in the pleural fluid raised concerns for a possible aspiration or an esophageal leak since it is commonly found in the gastrointestinal tract as well as various foods, juices, fruits, beverages, and probiotics. However, a swallow study showed no sign of contrast leakage. The patient was continued on fluconazole to target the S. cerevisiae from his empyema. He clinically improved with resolution of fevers and leukocytosis and repeat pleural fluid and blood cultures remained negative. Unfortunately, the patient developed a chyle leak producing a large chylothorax and heart failure with severe decompensation requiring re-intubation. At that point, he was transitioned to comfort care measures and expired shortly thereafter.

Question 1: What are probable/possible diagnoses?

Microbiology/Diagnostic Tests Performed: Pleural Fluid Analysis, Pleural Fluid Culture

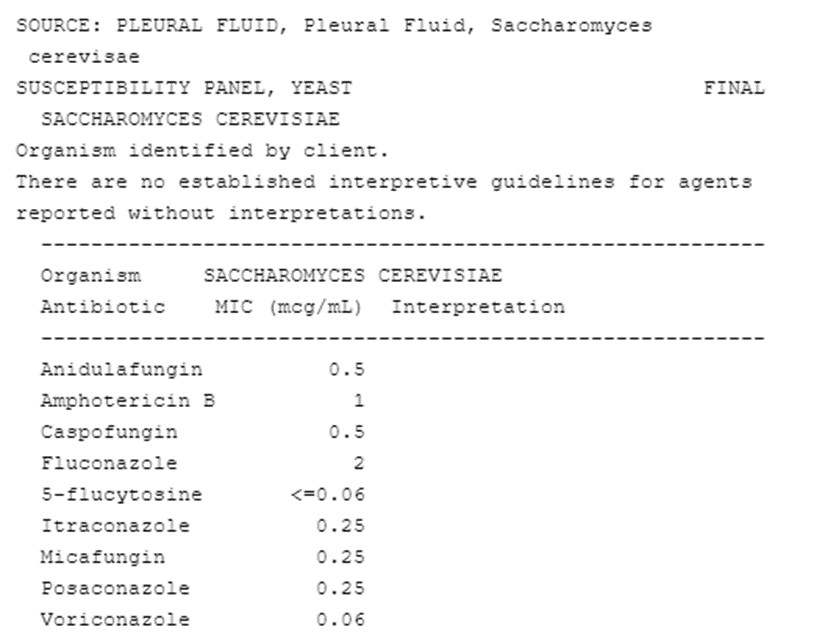

Table 1: Pleural Fluid Yeast Susceptibility Panel

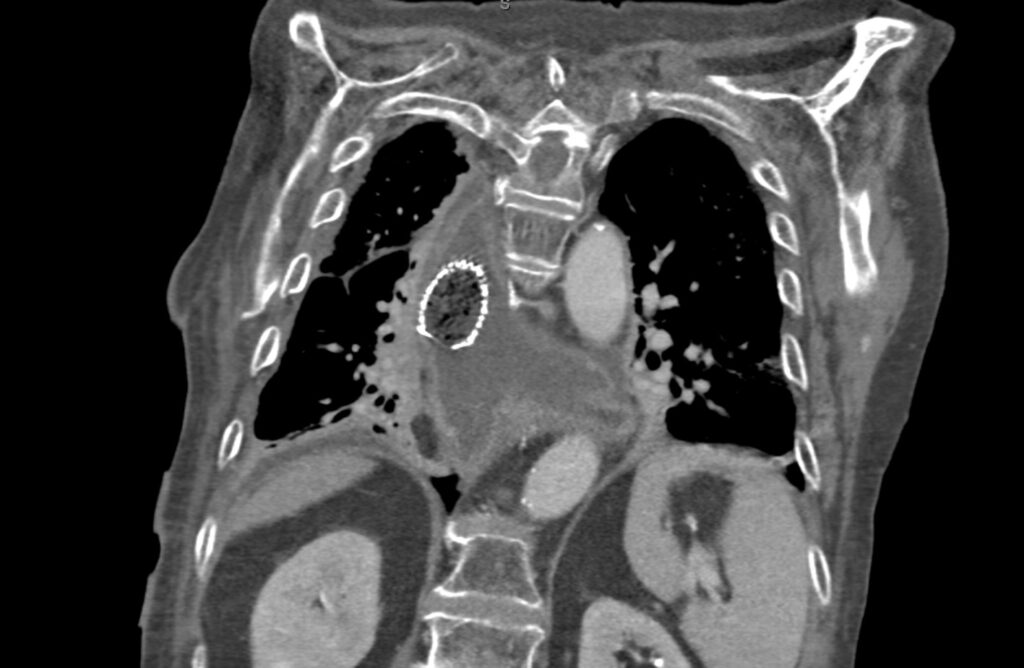

Figures 1 & 2: Computed Tomography (CT) chest with IV contrast showed perforation of gastric pull-through and communication with the medial mid to inferior posterior right pleural surface. Extensive loculated hydropneumothoraces involve the right hemithorax with complete right lung atelectasis, concerning for early complex empyema. Small, localized collection of previously administered at oral barium and retained material immediately inferior to the left of the proximal anastomosis may represent a diverticulum or loculated collection in communication with the pull-through element. No evidence of pneumomediastinum or mediastinitis. Left lung moderate pulmonary edema.

Final Diagnosis: Saccharomyces cerevisiae Empyema

Question 2: What treatment is recommended in the care of this patient?

Treatment: Intravenous Liposomal Amphotericin B and Fluconazole

Outcome: Fatal

Discussion:

S. cerevisiae is typically considered non-pathologic, however the implications of this pathogen as it pertains to critically ill patients is not fully understood (1). The potential for this pathogen to become invasive is thought to be contributed to by factors such as critical illness, central venous catheters, immunosuppression, and colonization with prior probiotic use (1-4). The diagnosis of S. cerevisiae infections can be difficult due to the non-specific clinical presentation and the recovery of S. cerevisiae from a sterile site. In fact, it should no longer be regarded as a non-pathologic fungus (5). Our case was further complicated by the pleural cavity being exposed to the esophageal contents, a body site that is frequently colonized with S. cerevisiae without the presence of fungemia. Invasive infections with this organism are found in patients with probable colonization of the digestive tract from food or probiotics along with the translocation of luminal contents via the GI tract. However, many of these patients also have conventional risk factors for invasive fungal infections such as central venous catheters, prolonged ICU stays and broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy (1). It appears one commonality between S. cerevisiae is the use of probiotics since these infections are generally secondary to translocation via the gastrointestinal mucosa (5).

Overall, fungal empyemas carry a high mortality rate (as high as 70%) and have poorer surgical outcomes when compared with bacterial empyemas (3). In one study, 30-day post thoracoscopic decortication mortality was reported to be 21.4% in fungal empyemas versus 5.9% in bacterial empyemas, p<0.001 (2). Risk factors for invasive Saccharomyces infections are similar to those with other invasive fungal infections, chiefly critically ill, immunocompromised patients on broad spectrum antimicrobials (3-4). Despite the rarity of invasive S. cerevisiae infections, there has been a recent increase in reported cases since the 1990s (4). Drug of choice for these infections includes intravenous (IV) liposomal amphotericin B or fluconazole. It is important to note that clinical trials evaluating therapy for S. cerevisiae have not been performed. However, one study reported susceptibilities which remained constant for amphotericin B (MIC90, 0.5–1 mcg/mL) and flucytosine (MIC90, 0.25 mcg/mL), while different rates of resistance to fluconazole and itraconazole have been described (1,5). Despite the unknown breakpoints for acceptable MICs for fluconazole and itraconazole, they are thought to be higher than those for C. albicans (4). There is data that supports amphotericin B as the likely antifungal of choice, but fluconazole MICs are often acceptable and numerous cases are reported with successful treatment (4). In vitro susceptibility testing should be performed on all cases of invasive Saccharomyces infections (1). The efficacy of cases using amphotericin B or fluconazole could also be somewhat related to central venous catheter removal or the theoretical low virulence of S. cerevisiae. It is important to note that despite the high mortality rate, this is not purely attributed to the fungal infection, but to the association of numerous co-morbidities seen in these patients (1,4).

In a comprehensive review of outcomes in 84 patients with invasive Saccharomyces infections, 68.7% (57/84) had favorable outcomes (4). Patients with S. boulardii infection had a better prognosis compared to those with S. cerevisiae infection (73% vs. 55.5%, p <0.01) (4). The rates of favorable outcome among immunocompromised patients and immunocompetent individuals did not differ significantly (65.5% vs. 73.8%) and there was no significant difference in those patients treated with amphotericin B (77.7%) and those receiving fluconazole (60%) (4). There are case reports describing S. cerevisiae as a cause of fungemia, peritonitis, endocarditis, vaginitis, pulmonary infections, and UTIs. However, empyema due to this organism is extremely rare. This case highlights the importance of an organism that is commonly used in food and beverage products that via colonization of mucosal surfaces can lead to invasive disease in critically ill immunocompromised patients. Though previously thought to be non-pathogenic, Saccharomyces is gradually becoming a more common cause of invasive disease with an associated high mortality rate (1-2).

References:

- Colombo, RE., & Vazquez, JA. (2023). Infections due to non-candidal yeasts. Diagnosis and Treatment of Fungal Infections, 167–182. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-35803-6_10

- Lahue, C., Madden, AA., Dunn, RR., et al. (2020). History and domestication of saccharomyces cerevisiae in bread baking. Frontiers in Genetics, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2020.584718

- Cheng, YF., Chen, CM., Chen, YL., et al. (2023). The outcomes of thoracoscopic decortication between fungal empyema and bacterial empyema. BMC Infectious Diseases, 23(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-022-07978-z

- Enache-Angoulvant, A., & Hennequin, C. (2005). Invasive saccharomyces infection: A comprehensive review. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 41(11), 1559–1568. https://doi.org/10.1086/497832

- Munoz, P., Bouza, E., Cuenca-Estrella, M., et al. (2005). Saccharomyces cerevisiae fungemia: An emerging infectious disease. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 40(11), 1625–1634. https://doi.org/10.1086/429916