Title: A Case of Fungal Endophthalmitis

Submitted by: Myint Noe, MD; Alexander Vostal, MD; Jonathan Jacobs, MD; John Baddley, MD

Institution: University of Maryland

Email: mnoe@som.umaryland.edu

Date Submitted: 5/17/2021

History:

A 70-year-old female with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and prolonged neutropenia, status post 5 cycles of azacitidine and venetoclax, presented to the emergency department with two days of swelling around the left eye and progressively worsening pain of the eye, especially with eye movement. She attributed it to her surgical mask scratching the affected eye while she was lying on her stomach during a bone marrow biopsy procedure three days ago. She denied other eye trauma. The patient did not use contact lenses. She complained of intermittent bilateral epistaxis but denied fever, chills, double vision, flashes, or floaters. She was receiving prophylaxis with levofloxacin, fluconazole, and valacyclovir. The patient was hemodynamically stable and afebrile on presentation. Ocular examination demonstrated significant ecchymosis, erythema, and edema of the left upper eyelid with tenderness to palpation, chemosis of the sclera and conjunctiva, and diffuse external ocular muscle restriction. Initial CT imaging showed left orbital proptosis with intra- and extraconal fat stranding surrounding the globe concerning for endophthalmitis without sinus pathology or intracranial extension. Chest CT showed new right middle lobe collapse/consolidation. She was started on vancomycin and meropenem.

Physical Examination:

Slit-lamp examination of the patient’s left eye exhibited significant ecchymosis, erythema, edema of the eyelid, hemorrhagic chemosis of the conjunctiva, and significant cells and flares within the anterior chamber. The left fundus was unable to be visualized due to haziness. The patient was also found to have diffuse restriction of the external ocular muscles on the left side, especially abduction and infraduction. Pupils were both round and reactive.

Examination of her right eye showed no significant abnormality.

Laboratory Examination:

On initial presentation:

WBC: 0.8 K/mcL

ANC: 0.22 K/mcL

Hemoglobin: 8.3 gm/dl

Platelet count: 24 K/mcl

Creatinine: 0.58 mg/dl

AST 20 U/l

ALT 14 U/l

Bilirubin 0.7 mg/dl

Blood cultures: no growth after 5 days.

Serum Aspergillus galactomannan antigen: negative

Serum cryptococcal antigen: negative

Urine Histoplasma antigen: negative

Question 1: What are probable/possible diagnoses?

The patient developed a rapid decline in left eye vision with worsening swelling on day 5. The patient was taken to the OR for vitrectomy with vitreous biopsy and had an intravitreal injection of vancomycin, ceftazidime, foscarnet, and voriconazole.

Worsening endophthalmitis while on systemic broad-spectrum antibiotics and fluconazole prophylaxis with a short interval to vision loss suggested infectious etiology and differential diagnoses include drug-resistant bacteria and fungi. Rarely, viruses such as HSV, VZV, CMV can disrupt the ocular blood barrier predisposing bacterial and fungal seeding. Given her history of AML, leukemic infiltration of the eye was also considered.

Microbiology/Diagnostic Tests Performed:

- Initial corneal scraping cultures of the left eye showed moderate growth of coagulase-negative staphylococcus and rare Acinetobacter radioresistens.

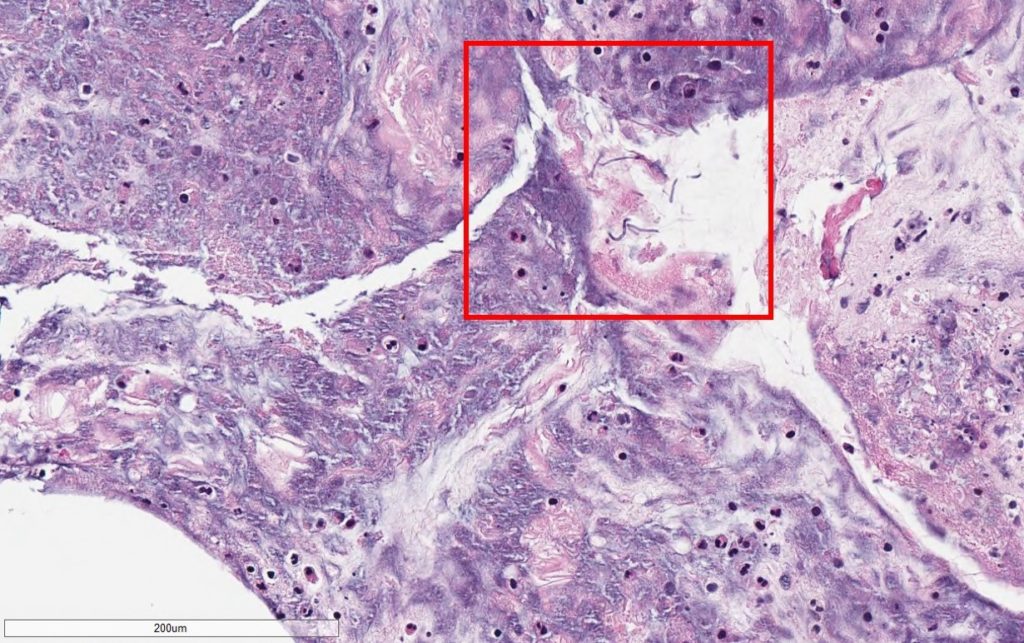

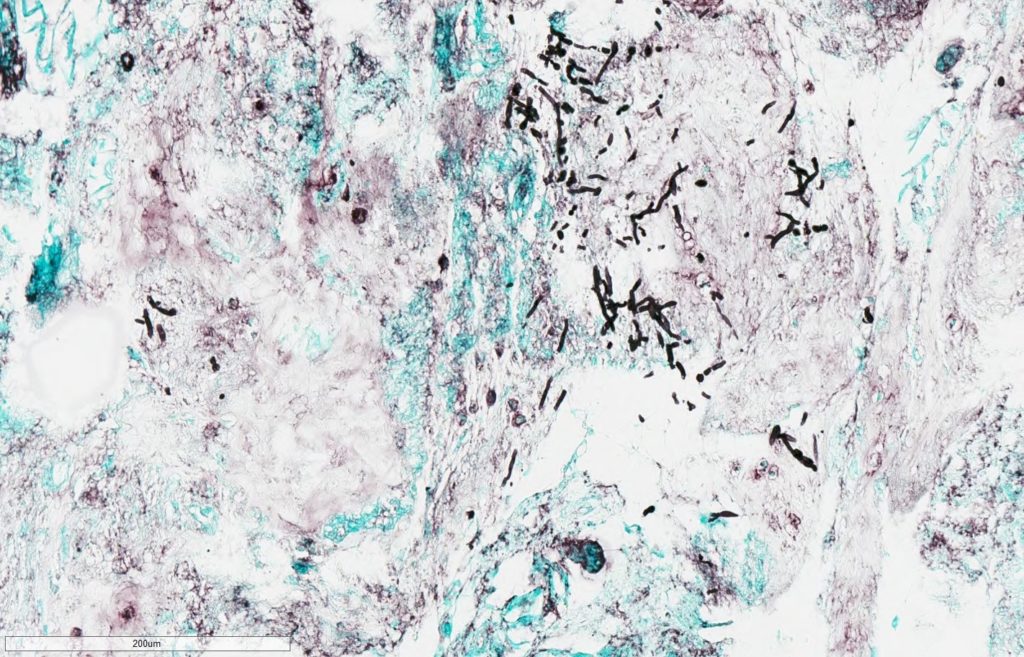

- Pathology for vitreous fluid reported no malignant cells but positive for thin, septated fungal hyphal forms on GMS stain (Figure 1A,1B).

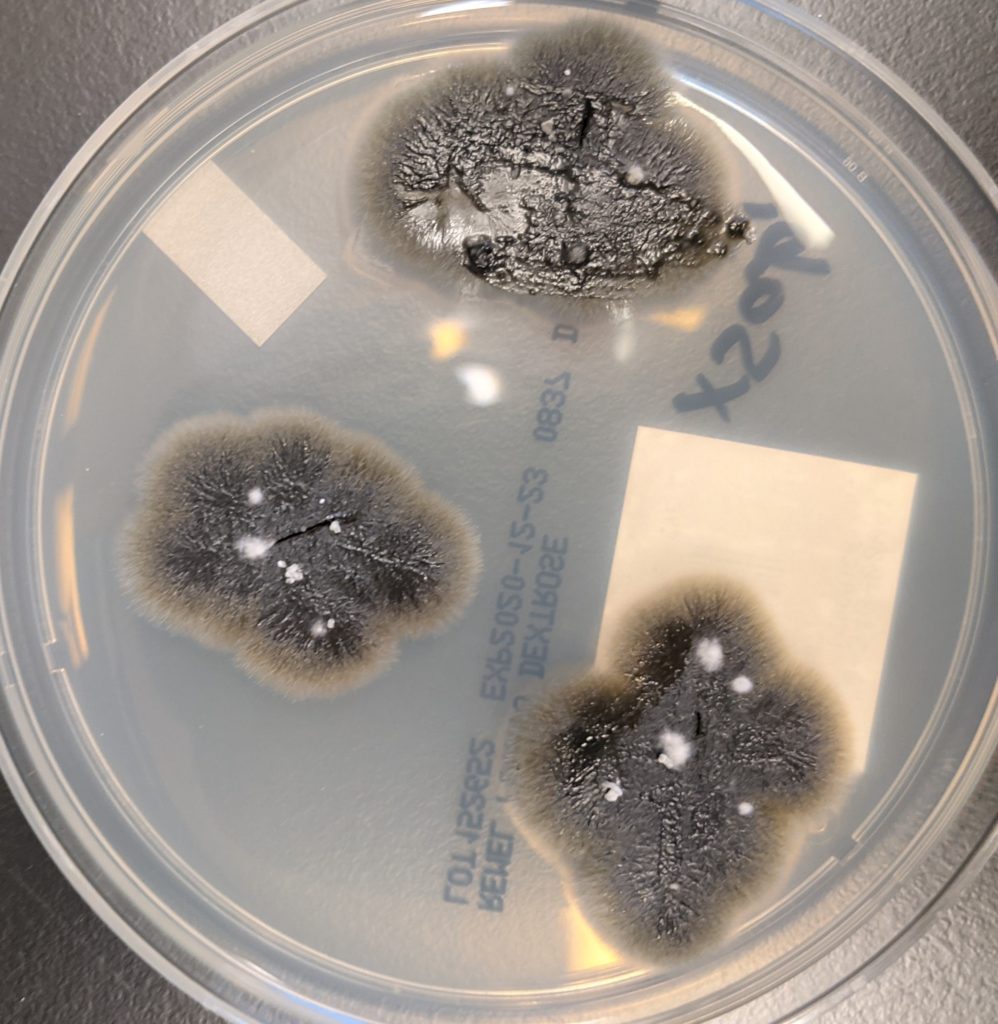

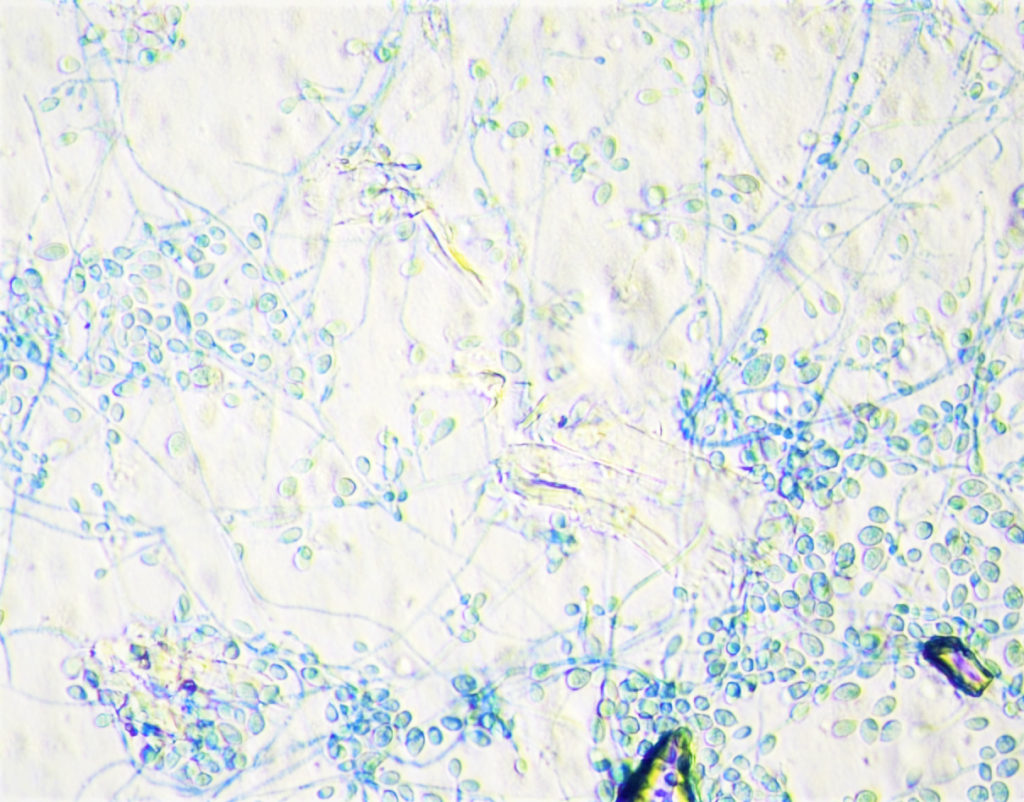

- Eventually, vitreous fluid fungal culture grew gray to black mold colonies (Figure 2). It was identified by MALDI-TOF as Lomentospora prolificans (Figure 3).

Final Diagnosis: Lomentospora prolificans Endophthalmitis

Question 2: What treatment is recommended in the care of this patient?

Treatment:

Initially, the patient was started on IV 3mg/kg of liposomal amphotericin B after vitrectomy. After thin septated hyphae were reported on vitreous fluid GMS stain, liposomal amphotericin B dose was increased to 5mg/kg, and posaconazole was added to the regimen. As Lomentospora prolificans is typically resistant to all available antifungal therapies, once it was identified from vitreous fluid culture, the antifungal regimen was changed to voriconazole and terbinafine. In addition, the patient underwent enucleation of the left eye; clear margins were obtained. As expected, susceptibility testing demonstrated resistance to all classes of antifungals tested with a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of >8 mcg/mL for amphotericin B, > 8 mcg/mL for micafungin, > 16 mcg/mL for both posaconazole and voriconazole.

Outcome:

The patient had an excellent post-op response with no concern for residual infection since discharge from the hospital. She has since restarted on remaining cycles of chemotherapy and remained on voriconazole and terbinafine.

Discussion:

Lomentospora prolificans (formerly Scedosporium prolificans) is a rare environmental fungus that is closely related to the genus Scedosporium. The environmental habitat of L. prolificans was initially thought to be isolated to Australia and Spain, but it has since demonstrated a global distribution [1]. Scedosporium spp. have a predilection for human environments, such as soil in urban or industrial/agricultural areas [2].

Since Scedosporium spp. were first described as infectious agents in the 1980s, they have been associated with human infection in both immunocompetent hosts, via direct inoculation by trauma or near-drowning, and immunocompromised hosts [3,4]. Both solid organ transplant (SOT) and hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) recipients appear to suffer a proportionally large burden of Lomentospora/Scedosporium spp. infections. A quarter of non-aspergillus mold infections in transplant recipients are due to either Lomentospora prolificans or Scedosporium apiospermum [5]. Lung transplant recipients accounted for the majority of SOT patients with a microbial culture positive for Lomentospora/Scedosporium spp., but this more frequently represented colonization versus an active infection [6]. In contrast, HSCT patients more often present with disseminated disease [7]. Hematologic malignancies, especially those with neutropenia and advanced human immunodeficiency virus infections, have also been associated with disseminated Lomentospora/Scedosporium spp. Infections [8, 9].

Colonization with Lomentospora spp. has been best described in patients with chronic lung disease, such as cystic fibrosis [1]. Disseminated disease states, such as central nervous system, endocarditis/vascular, and systemic infection, present almost exclusively in severely immunocompromised hosts. Localized disease has been described in the skin, soft tissue, bone, and ocular tissue [3]. Ocular infections such as keratitis can present with local pain, lacrimation, decreased visual acuity, and photophobia in immunocompetent hosts and are associated with trauma to the eye from contact lenses or foreign bodies. A delay in diagnosis of pre-existing Lomentospora/Scedosporium spp. keratitis in combination with mistaken treatment with antibiotics or steroids can lead to contiguous spread of infection and endophthalmitis. Metastatic spread of Scedosporium spp. infection has also been implicated in endophthalmitis, especially in immunocompromised hosts [3].

Treatment of L. prolificans represents a unique paradigm in antimicrobial therapy of mold infections, as it has demonstrated resistance to all classes of antifungal therapeutic agents—with the exception of voriconazole at elevated serum levels. Multiple combination therapies have been proposed, such as either voriconazole or liposomal amphotericin B plus terbinafine, but data on clinical outcomes remains inconclusive. Additional studies have proposed combining antifungal therapy with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Ultimately, the return of innate immune cells with phagocytic function, i.e., neutrophils and surgical resection with clean margins, offer the patient the greatest chance of survival [10]. Unfortunately, overall mortality from L. prolificans infection is as high as 85.7% in immunocompromised patients with malignancy [11].

Key References:

- Subedi S, Chen S. Epidemiology of Scedosporiosis. Curr Fungal Infect Rep. 2015;9(4):275-284.

2. Kaltseis J, Rainer J, De Hoog GS. Ecology of Pseudallescheria and Scedosporium species in human-dominated and natural environments and their distribution in clinical samples. Med Mycol. 2009;47(4):398-405.

3. Ramirez-Garcia A, Pellon A, Rementeria A, et al. Scedosporium and Lomentospora: an updated overview of underrated opportunists. Med Mycol. 2018;56(suppl_1):102-125.

4. Cortez KJ, Roilides E, Quiroz-Telles F, et al. Infections caused by Scedosporium spp. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21(1):157-197.

5. Husain S, Alexander BD, Munoz P, et al. Opportunistic mycelial fungal infections in organ transplant recipients: emerging importance of non-Aspergillus mycelial fungi. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37(2):221-229.

6. Johnson LS, Shields RK, Clancy CJ. Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and outcomes of Scedosporium infections among solid organ transplant recipients. Transpl Infect Dis. 2014;16(4):578-587.

7. Husain S, Muñoz P, Forrest G, et al. Infections due to Scedosporium apiospermum and Scedosporium prolificans in transplant recipients: clinical characteristics and impact of antifungal agent therapy on outcome. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(1):89-99.

8. Tammer I, Tintelnot K, Braun-Dullaeus RC, et al. Infections due to Pseudallescheria/Scedosporium species in patients with advanced HIV disease–a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Int J Infect Dis. 2011;15(6):e422-e429.

9. Jenks JD, Seidel D, Cornely OA, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of invasive Lomentospora prolificans infections: Analysis of patients in the FungiScope ® registry. Mycoses. 2020;63(5):437-442.

10. Pellon A, Ramirez-Garcia A, Buldain I, et al. Pathobiology of Lomentospora prolificans: could this species serve as a model of primary antifungal resistance? Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2018;51(1):10-15.

11. Seidel D, Meißner A, Lackner M, et al. Prognostic factors in 264 adults with invasive Scedosporium spp. and Lomentospora prolificans infection reported in the literature and FungiScope ®. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2019;45(1):1-21.