Title: The Tell-Tale Heart(s), Part 1: Donor-Derived Invasive Fungal Infections among Heart Transplant Recipients

Submitted by: Jay Krishnan, John Dougherty, Joseph Barwatt, Manuela Carugati, Rachel Miller, Cameron Wolfe, John Perfect, Julia Messina

Institution: Duke University

Email: jrk26@duke.edu

History

A 54-year-old man status post remote orthotopic heart transplantation for non-ischemic cardiomyopathy complicated by cardiac allograft vasculopathy was admitted for redo orthotopic heart transplantation.

Donor History: The organ donor was a 33-year-old man with a history of intravenous drug use, who was found unconscious with a package of white crystalline substance thought to be methamphetamines adjacent to his body. During his hospitalization, he progressed to brain death in the setting of intracranial hemorrhage. Organ procurement was performed three days after the donor’s admission.

The recipient’s immediate post-transplant course was notable for hemorrhage prompting prolonged open chest, cardiogenic shock, and acute kidney injury. During this time, he was placed on antimicrobial prophylaxis with vancomycin, cefazolin, fluconazole, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, inhaled amphotericin B, and acyclovir in accordance with institutional post-transplantation and open chest protocols.

After chest closure on post-operative day five, the recipient was noted to be mildly confused and had a persistent leukocytosis. The recipient denied focal complaints other than expected post-operative pain. The Infectious Diseases team was consulted and recommended routine blood cultures.

Physical Examination:

Temperature 36.8 Celsius on continuous renal replacement therapy, heart rate 107/min, blood pressure 103/66 mmHg, respiratory rate 22/min, on oxygen 1L/min nasal cannula.

General: Mildly lethargic, in no acute distress

Psych: Oriented to person, place, and time. Short-term recall mildly impaired.

Eyes: PERRL, EOMI, conjunctiva clear, anicteric sclera

Neck: Supple and no adenopathy. Mild R neck ecchymoses from central line attempts

HENT: Oropharynx clear, dry mucous membranes, no lesions

Cardiovascular: Normal rate and regular rhythm without murmurs, rubs or gallops

Respiratory: CTAB anteriorly, no focal crackles

Abdomen: soft, nontender, nondistended, normoactive bowel sounds

Extremities: 1+ bilateral lower extremity edema. Bilateral femoral lines without surrounding erythema, warmth, induration, or drainage

Skin: No rashes or lesions

Surgical Site Exam: median sternotomy well-approximated without surrounding erythema/fluctuance. Mediastinal drain with serosanguinous output

Laboratory Examination:

WBC: 28,100 cells/microL, Hemoglobin: 9.5 g/dL, Platelet: 75/microL, Creatinine 2.2 ml/dL on continuous renal replacement therapy, AST 47 U/L, ALT 8 U/L, Alkaline Phosphatase 83 U/L, Total Bilirubin 1.8 mg/dL.

Radiology:

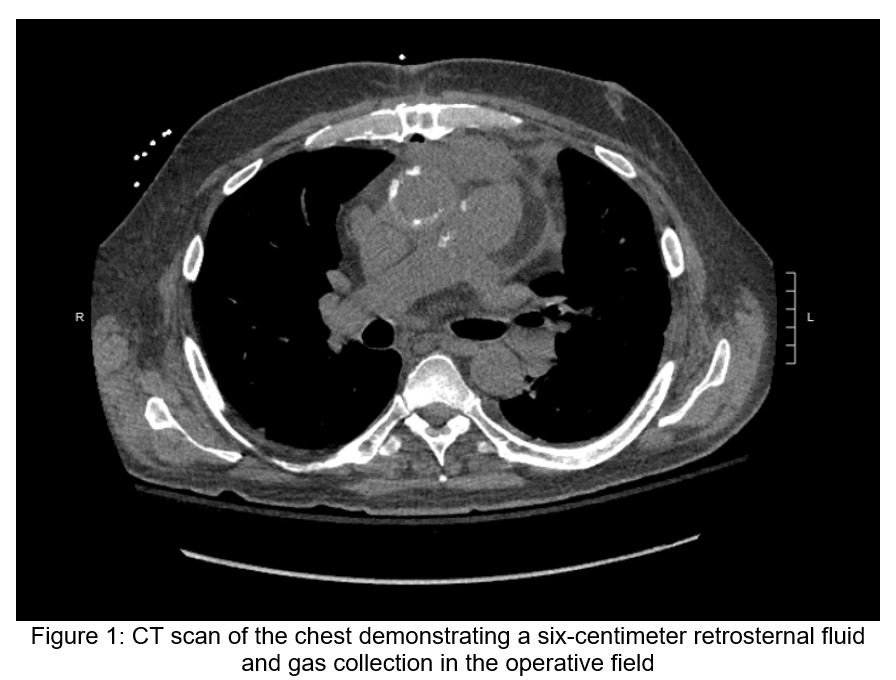

Post-operative transesophageal echocardiography demonstrated normal left ventricular function, moderate right ventricular dysfunction, and mild mitral regurgitation without evidence of vegetations or other valvular abnormalities. Chest radiography was unremarkable. A chest CT (Figure 1) demonstrated a six-centimeter retrosternal fluid and gas collection in the operative field.

Question 1: What are probable/possible diagnoses?

The differential diagnosis for leukocytosis and delirium in the early post-operative heart transplant patient is broad and may not necessarily reflect infection. Nonetheless, close evaluation for common nosocomial infections, including surgical site infection, pneumonia, central line-associated bloodstream infection, and urinary tract infections, should be pursued. The six-centimeter retrosternal fluid collection should be investigated as a potential source of infection though its presence could also simply reflect a sterile, reactive collection in the immediate post-operative state. Finally, particularly in the early post-operative period, donor-derived infections are also a consideration.

Microbiology/Diagnostic Tests Performed:

Donor blood and renal tissue cultures were notable for late growth of Candida metapsilosis (blood cultures, one out of two sets, reported positive 8 days after collection while renal tissue cultures were reported positive three days after collection). The recipient blood cultures returned positive for Candida metapsilosis 7 days after organ procurement.

The patient was started on micafungin 100 mg daily and underwent removal of all central lines. Repeat transthoracic and later transesophageal echocardiography showed no evidence of valvular vegetations or abnormalities of any anastomotic sites. Ophthalmologic examination showed no evidence of fungal endophthalmitis.

The patient remained persistently fungemic with Candida metapsilosis despite line removal and increasing micafungin therapy to 150mg daily. Ultimately, the patient underwent sternal debridement of the retrosternal fluid collection and operative cultures from the mediastinum and pleural fluid collections grew Candida metapsilosis.

Final Diagnosis:

Donor-derived Candida metapsilosis fungemia with mediastinitis and suspected sub-radiographic endocarditis in a heart transplant recipient.

Question 2: What treatment is recommended in the care of this patient?

Treatment:

Despite five operative sternal wound debridements, repeated intravascular line exchanges, and ongoing micafungin therapy over the upcoming weeks, the recipient’s blood cultures through post-operative day 25 continued to grow Candida metapsilosis. Liposomal amphotericin B 3mg/kg daily was added to micafungin 150mg daily, and blood cultures cleared by post-operative day 30.

Susceptibilities for the Candida metapsilosis returned with the following minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs): fluconazole 32 mcg/mL, micafungin 0.25 mcg/mL, and voriconazole 0.016mcg/mL. The liposomal amphotericin B was discontinued approximately four weeks after blood culture clearance, and the recipient was maintained on micafungin 100mg daily for close to 6 weeks after discharge with persistent culture negativity thereafter.

Outcome:

As an outpatient, the recipient was started on voriconazole and bridged with micafungin for close to 3 weeks. His voriconazole levels initially ranged from 1.1-1.9 mcg/mL for two to three weeks but subsequently stabilized between 2-3 mcg/mL.

Two months after transitioning to voriconazole and nearly five months after his last positive blood culture, the recipient reported a two-week history of fatigue and diffuse myalgias to his Infectious Diseases provider. Blood cultures were repeated and returned positive for Candida metapsilosis. He was readmitted, and micafungin 150mg daily was added to voriconazole. The patient underwent an extensive work-up for persistent source of infection including repeat transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography, venous duplex studies, and positron emission tomography scan, all of which did not reveal an obvious endovascular source of infection. Because of mild non-specific FDG-avidity of his post-operative sternal fragments, the patient underwent a sternal bone biopsy in the operating room, which did not show microbiologic evidence of fungal organisms. During this procedure, Sternal bone appeared healthy upon inspection without evidence of osteomyelitis.

The recipient was transitioned from voriconazole and micafungin to liposomal amphotericin B 3mg/kg daily and micafungin. Flucytosine 25 mg/kg four times daily was added after persistent culture positivity after two weeks of combined amphotericin B and micafungin therapy. Repeat voriconazole MIC testing revealed an increase to 2 mcg/mL from 0.016 mcg/mL, concerning for the development of voriconazole resistance. Ultimately, his fungemia cleared on liposomal amphotericin B, micafungin, and flucytosine after nearly 3 weeks of positive blood cultures. He was transitioned to posaconazole, micafungin, and flucytosine on discharge for four more weeks, and he ultimately has been maintained on posaconazole and flucytosine for 11 months thus far without relapse.

Discussion: (500 words)

Here, we describe a case of donor-derived Candida metapsilosis infection in the early post-operative period after redo heart transplantation. The donor, who had a history of intravenous drug use, likely had subclinical Candida endocarditis prior to organ procurement, as suggested by the blood cultures and bilateral kidney parenchymal cultures that returned positive after organ transplantation. This sub-radiographic endovascular infection was transplanted along with the donor’s heart into the recipient, which resulted in persistent fungemia and mediastinitis. The recipient required aggressive surgical debridement to manage his Candida mediastinitis in addition to prolonged combination antifungal therapy to clear his bloodstream though he would suffer from relapsed infection several months later.

Donor-derived invasive fungal infections (IFIs) among solid organ transplant recipients are rare occurrences that carry significant morbidity and mortality. A 2020 report from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) found that unexpected donor-derived IFIs affected around 2 out of every 10,000 solid organ transplant recipients between 2008 and 2017 in the United States.1 In this report, transmission of Candida species from organ donor to recipient comprised nearly 25% of all described cases. Notably, contamination of preservation fluid is considered to be the most common cause of donor-derived candidiasis associated with kidney and liver transplantation. Infection transmission from donors with candidemia is considered rare, particularly among heart transplant recipients.2

As the organ donor pool expands to include those with higher-risk comorbidities and behaviors, we must be vigilant for subclinical infections in the organ donor. Risk factors for invasive Candida infections such as endocarditis and mediastinitis include intravenous drug abuse, recent chemotherapy for cancer treatment, prolonged presence of central venous catheters, and prior valvular damage or surgery.3

Management of Candida endocarditis, regardless of transplantation status, involves both surgical intervention with valve replacement and antifungal therapy with either high-dose echinocandin therapy or liposomal amphotericin B 3-5mg/kg daily with or without flucytosine 25 mg/kg 4 times daily.3-5 Candida mediastinitis should be managed similarly with both antifungal and surgical therapy including mediastinal debridement. However, even with appropriate therapy, mortality from Candida infective endocarditis is estimated to be between 25-50% at 1 year with worse outcomes noted among those who do not undergo surgery.5-7,10

This case had two notable therapeutic complications: 1) persistent candidemia despite mediastinal debridement and antifungal monotherapy and 2) relapsed candidemia several months after culture clearance. While endovascular involvement was suspected both during his initial and subsequent presentations, no radiographic evidence of intracardiac or intravascular infection was found that could have been surgically targeted. Relapse of infection can occur with Candida endovascular infections, which in part may be due to the ability of Candida to form biofilms.6-7

In an effort to reduce the incidence of these complications, combination antifungal therapy has been suggested for therapy of primary, refractory, and relapsed Candida endovascular infections for several reasons. These include the potential for additive or synergistic efficacy, reduced risk of resistance, and ability to dose-reduce antifungals to limit toxicities.8 While randomized trials have not been conducted, in vitro studies and case reports have suggested success with combination therapy. Liposomal amphotericin B, for instance, has shown promising in vitro synergistic activity with both echinocandins and posaconazole, Flucytosine is frequently employed in severe cases of invasive candidiasis (such as Candida meningitis) in combination with liposomal amphotericin B.8-9 A combination azole-flucytosine step-down regimen was employed after our patient’s infection relapsed as these agents have different mechanisms of action and the demonstrated efficacy of flucytosine for other severe invasive fungal syndromes.

In summary, donor-derived IFIs among heart transplant recipients are rare events with often devastating consequences. The donor’s medical history should be evaluated for unexplained clinical and any evidence of fungal infection in the donor warrants meticulous evaluation for IFI in the recipient. Management of the recipient should subsequently be tailored to the specific transplanted organ, which, in heart transplant recipients, necessitates evaluation and/or treatment for endocarditis and mediastinitis.

TO BE CONTINUED…

Key References:

- Kaul DR, Vece G, Blumberg E, La Hoz RM, Ison MG, Green M, Pruett T, Nalesnik MA, Tlusty SM, Wilk AR, Wolfe CR, Michaels MG. Ten years of donor-derived disease: A report of the disease transmission advisory committee. Am J Transplant. 2021 Feb;21(2):689-702. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16178.

- Singh N, Huprikar S, Burdette SD, Morris MI, Blair JE, Wheat LJ; American Society of Transplantation, Infectious Diseases Community of Practice, Donor-Derived Fungal Infection Working Group. Donor-derived fungal infections in organ transplant recipients: guidelines of the American Society of Transplantation, infectious diseases community of practice. Am J Transplant. 2012 Sep;12(9):2414-28. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04100.x.

- Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, Clancy CJ, Marr KA, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Reboli AC, Schuster MG, Vazquez JA, Walsh TJ, Zaoutis TE, Sobel JD. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Candidiasis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Feb 15;62(4):e1-50. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ933. Epub 2015 Dec 16. PMID: 26679628; PMCID: PMC4725385.

- Jordan AM, Tatum R, Ahmad D, Patel SV, Maynes EJ, Weber MP, Moss S, Royer TL, Tchantchaleishvili V, Massey HT, Rame JE, Zurlo JJ, Aburjania N. Infective endocarditis following heart transplantation: A systematic review. Transplant Rev (Orlando). 2022 Jan;36(1):100672. doi: 10.1016/j.trre.2021.100672. Epub 2021 Nov 6. PMID: 34826752.

- Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, Fowler VG Jr, Tleyjeh IM, Rybak MJ, Barsic B, Lockhart PB, Gewitz MH, Levison ME, Bolger AF, Steckelberg JM, Baltimore RS, Fink AM, O’Gara P, Taubert KA; American Heart Association Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and Stroke Council. Infective Endocarditis in Adults: Diagnosis, Antimicrobial Therapy, and Management of Complications: A Scientific Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015 Oct 13;132(15):1435-86. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000296.

- Steinbach WJ, Perfect JR, Cabell CH, Fowler VG, Corey GR, Li JS, Zaas AK, Benjamin DK Jr. A meta-analysis of medical versus surgical therapy for Candida endocarditis. J Infect. 2005 Oct;51(3):230-47. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2004.10.016. Epub 2004 Dec 1. PMID: 16230221.

- Mamtani S, Aljanabi NM, Gupta Rauniyar RP, Acharya A, Malik BH. Candida Endocarditis: A Review of the Pathogenesis, Morphology, Risk Factors, and Management of an Emerging and Serious Condition. Cureus. 2020 Jan 18;12(1):e6695. doi: 10.7759/cureus.6695.

- Livengood SJ, Drew RH, Perfect, JR. Combination Therapy for Invasive Fungal Infections. Curr Fungal Infect Rep 2020 Jan 16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12281-020-00369-4

- Chaturvedi V, Ramani R, Andes D, Diekema DJ, Pfaller MA, Ghannoum MA, Knapp C, Lockhart SR, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Walsh TJ, Marchillo K, Messer S, Welshenbaugh AR, Bastulli C, Iqbal N, Paetznick VL, Rodriguez J, Sein T. Multilaboratory testing of two-drug combinations of antifungals against Candida albicans, Candida glabrata, and Candida parapsilosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011 Apr;55(4):1543-8. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01510-09.

- Arnold CJ, Johnson M, Bayer AS, Bradley S, Giannitsioti E, Miró JM, Tornos P, Tattevin P, Strahilevitz J, Spelman D, Athan E, Nacinovich F, Fortes CQ, Lamas C, Barsic B, Fernández-Hidalgo N, Muñoz P, Chu VH. Candida infective endocarditis: an observational cohort study with a focus on therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015 Apr;59(4):2365-73. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04867-14.