Title: Unusual facial lesions in a kidney transplant recipient

Submitted by: Liam Dalton, Carol A. Kauffman and Marisa H. Miceli

Institution: Univerisyt of Michigan

Email: mmiceli@med.umich.edu

Date Submitted: Novemeber 21, 2024

History:

A 23-year-old man, who had received a living related donor renal transplant in 2001 and who was taking mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus, and prednisone, underwent facial reconstruction surgery on 12/10/2021 to repair facial fractures sustained in an altercation. Three weeks later, he noted the onset of purulent bloody nasal discharge and cough with purulent brown sputum, intermittent fevers, chills, sweats, and shortness of breath. On admission, temperature was 100.5°F, and oxygen saturation was 95%. White blood cell (WBC) count was 6900/µL; serum creatinine was 2.2 mg/dL (baseline 1.6 mg/dL), serum tacrolimus concentration was 5.1 ng/mL (target 4-6 ng/mL). Computed tomography (CT) revealed complete opacification of the left maxillary sinus; chest radiograph showed interstitial infiltrates. Within 2 days, hypoxic respiratory failure and hypotension developed, and mechanical ventilation was initiated.

On the fourth day after admission, the Histoplasma urine antigen (MiraVista Laboratory, Indianapolis, IN) was reported as >20 ng/mL, and liposomal amphotericin B (L-AmB) 3mg/kg was started. Serum creatinine rose to 3.2 mg/dL. L-AmB and was discontinued after 7 days, and itraconazole, 200 mg twice daily, was begun. The patient’s respiratory status improved quickly; he was extubated after 3 days and was discharged on 1/19/2022. Ultimately, cultures of both blood and endoscopic sinus aspiration obtained on admission yielded H. capsulatum.

On follow-up, Histoplasma urine antigen levels were >20 ng/mL in February and May, and 12.05 ng/mL in December, 2022. Tacrolimus serum concentrations were high until the dosage was reduced by half while he was taking itraconazole. Itraconazole, 200mg BID, was continued for one year, ending in January 2023.

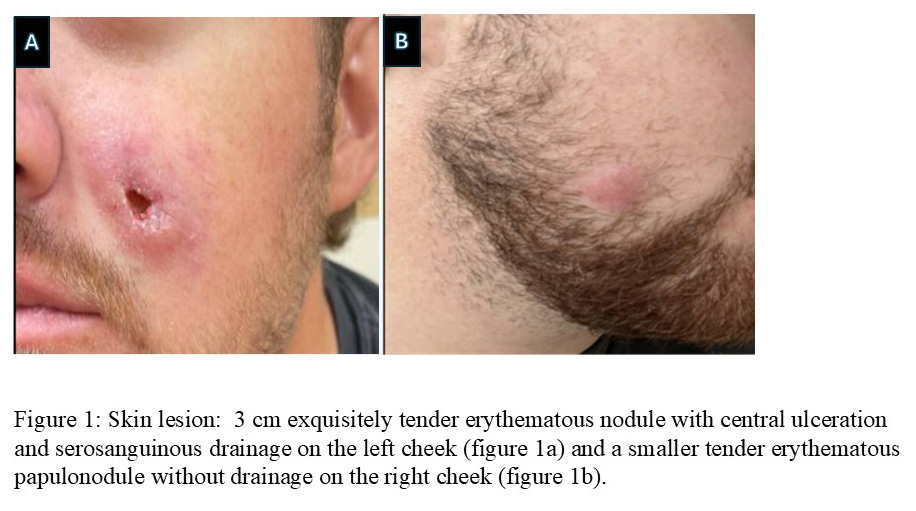

In February 2023, the tacrolimus serum concentration was <1.0 ng/mL, and serum creatinine had risen to 2.4 mg/dL. On 2/10/2023 he was treated with prednisone, 100 mg daily, for 3 days and on 2/23/2023 with prednisone, 200 mg daily, for 5 days for possible transplant rejection. In April, he noticed two facial lesions, and several weeks later developed chills and night sweats, followed by bloody sinus discharge, diarrhea, vomiting, and weight loss. By June, the left cheek lesion had enlarged, was painful, and drained serosanguinous fluid. A dermatologist performed an incision and drainage procedure and prescribed trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, but no improvement occurred. Because of progressive constitutional symptoms and worsening facial lesions, he was admitted to hospital in July 2023.

Physical Examination:

Blood pressure 118/55 mm Hg; heart rate 65 beats/min.; respirations 16; oxygen saturation 97% on room air; temperature 98.2oF

General: Healthy appearing young man

Cardiovascular: regular rhythm; No murmurs or extra sounds; pulses 2+ throughout

Pulmonary: clear to auscultation bilaterally

Abdomen: soft; non-tender; no hepatosplenomegaly

Skin: 3 cm exquisitely tender erythematous nodule with central ulceration and serosanguinous drainage on the left cheek (figure 1a) and a smaller tender erythematous papulonodule without drainage on the right cheek (figure 1b).

Laboratory Examination:

WBC: 4600/µL

Differential: 86% neutrophils, 6% lymphocytes, 6% monocytes, 1% eosinophils, 0.4% basophils, 0.6% immature granulocytes

Hemoglobin: 9.0 g/dL

Platelets: 174,000/µL

Creatinine: 2.1mg/dL

Alanine aminotransferase: 22 IU/L

Aspartate aminotransferase: 20 IU/L

Alkaline Phosphatase 67 IU/L

Question 1: What are probable/possible diagnoses?

Given the constellation of constitutional symptoms, the appearance of new skin lesions, and the prior history of disseminated histoplasmosis, the differential diagnosis in this renal transplant recipient included the following:

- Histoplasmosis

- Blastomycosis

- Nocardiosis

- Nontuberculous mycobacterial infection

Microbiology/Diagnostic Tests Performed:

– Computed tomography (CT)

Chest: Diffuse, bilateral centrilobular micronodules, involving all pulmonary lobes

Neck: Extensive bilateral neck lymphadenopathy

Maxillofacial: No sinonasal disease identified

– Skin of left cheek, punch biopsy:

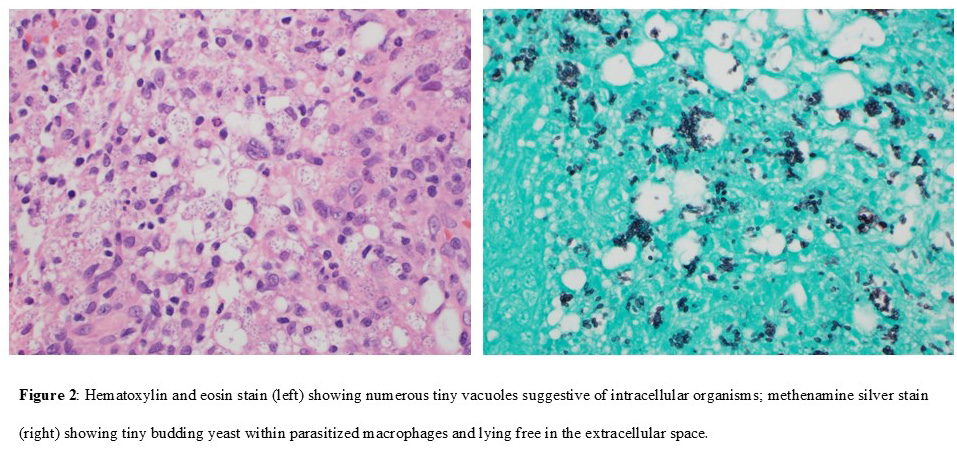

Hematoxylin and eosin stain: tiny vacuoles in many cells suggestive of intracellular organisms (figure 2a)

Methenamine silver stain: numerous 2-4 µm budding yeasts both inside macrophages and in extracellular spaces, consistent with H. capsulatum (figure 2b)

–Cultures:

Left cheek skin lesion: growth of white-tan mold with tuberculate conidia and smaller microconidia, later identified as H. capsulatum

Blood culture lysis-centrifugation system (isolator tube): no growth

H. capsulatum antibody studies

Complement fixation: yeast phase 1:8; histoplasmin 1:8

Histoplasma antigen enzyme immunoassay (EIA):

Serum: 6.44 ng/mL

Urine:>20 ng/mL

Final Diagnosis:

Recurrent disseminated H. capsulatum infection presenting with cutaneous manifestations

Question 2: What treatment is recommended in the care of this patient?

The IDSA guidelines for management of histoplasmosis recommend treating disseminated histoplasmosis with 3 mg/kg daily of L-AmB with alternatives of 5 mg/kg/day of another lipid formulation or 0.7-1mg/kg/day of amphotericin B deoxycholate for 1-2 weeks, followed by oral itraconazole for at least 12 months.

Treatment/Outcome:

This patient was treated with L-AmB 3 mg/kg IV daily; however, within 5 days of starting L-AmB, the serum creatinine had increased to 3 mg/dL. L-AmB was stopped, itraconazole was started, and the serum creatinine fell to his baseline of 2 mg/dL. All symptoms resolved within a month. Urine Histoplasma antigen was >20 ng/mL until November 2023, when it fell to 13.34 ng/mL; from January through September 2024 values remained between 2-5 ng/mL. Serum Histoplasma antigen varied from 0.5-5 ng/mL throughout this same period. Tacrolimus required many dose adjustments to achieve appropriate therapeutic serum levels.

Because of the complex drug-drug interaction between itraconazole and tacrolimus, itraconazole was changed to posaconazole, 300mg daily, and appropriate serum concentrations of tacrolimus were achieved. Further genotype testing revealed normal CYP3A4 activity, but reduced CYP3A5 activity with homozygous 3*/3* genotype. Antifungal therapy was stopped on 10/7/2024, and the patient will have careful follow-up with repeated clinical evaluation and antigen testing.

Discussion:

Infection with H. capsulatum is asymptomatic in most persons. When exposure does result in symptomatic infection, the manifestations most commonly are those of acute pulmonary infection. Disseminated infection is much less common and is more often found in immune compromised hosts, including persons with HIV, solid organ transplant recipients, and patients treated with corticosteroids, tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, or other immunosuppressive agents. This case illustrates several interesting issues in the care of a solid organ transplant recipient with disseminated histoplasmosis.

- Other disseminated fungal infections, such as blastomycosis and coccidioidomycosis, frequently present with cutaneous lesions in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients, but cutaneous manifestations associated with histoplasmosis are uncommon in immunocompetent persons. In immunocompetent persons, the syndrome of primary cutaneous inoculation histoplasmosis has been reported very rarely [1,2]. Similar to prosector’s nodule reported with tuberculosis, a localized infection results, systemic manifestations are absent, and the lesion heals with no anti-fungal therapy. This clearly was not the case with our patient.

The cutaneous manifestations of disseminated histoplasmosis are many and include subcutaneous nodules, crusted papules, erythematous indurated plaques, ulcers, abscesses, umbilicated lesions resembling molluscum, cellulitis, and necrotizing vasculitis [3]. In some regions of the world, especially Latin America, skin lesions are reported in as many as 40% to 66% of persons with HIV, but in the United States, many fewer persons with HIV (6-10%) are noted to manifest cutaneous involvement [4-6]. It has been postulated that this may relate to geographical variations in H. capsulatum strains [6]. Among solid organ transplant recipients, cutaneous lesions are not commonly seen; several reports have noted only 2-4% of patients with skin lesions [7-9].

Given our patient’s prior history of histoplasmosis and new onset skin lesions in the setting of several weeks of progressive constitutional symptoms, biopsy with histopathological examination and culture of the skin lesion held the clue to an early diagnosis but was not performed for several months. The occurrence of missed opportunities for early diagnosis of histoplasmosis has been emphasized repeatedly [10].

- Infection of the sinuses with disseminated histoplasmosis is rare. Mucocutaneous lesions in the oral cavity, pharynx, and anterior nares are not uncommon in patients with chronic disseminated histoplasmosis and may be the presenting symptom, but sinus infection without oropharyngeal involvement has been rarely reported [11,12]. Our patient’s initial presentation was following facial reconstruction. One could postulate that hematogenous spread of H. capsulatum occurred from an unrecognized pulmonary source to the sinuses that had been traumatized with either the initial fist fight or at the time of surgery.

- It is known that itraconazole, a CYP3A4 inhibitor, decreases the metabolism of tacrolimus; because of this effect, the tacrolimus dosage was decreased when antifungal therapy was started. However, the interaction was greater than that usually seen and was explained when it was found that the patient had reduced CYP3A5 activity [13]. Unfortunately, the drop in tacrolimus levels to unmeasurable within a month of discontinuing itraconazole after the first admission was likely because he continued to take an itraconazole-adjusted reduced dose of tacrolimus. This led to the possibility of rejection and the use of pulse steroid therapy, which likely contributed to reactivation of histoplasmosis.

Key References:

1. Tesh RB, Schneidau JD. Primary cutaneous histoplasmosis. N Engl J Med 1966;275(11):597-599.

2. Tosh FE, Balhuizen J, Yates JL, Brasher CA. Primary cutaneous histoplasmosis. report of a Case. Arch Intern Med 1964;114:118-119.

3. Chang P, Rodas C. Skin lesions in histoplasmosis. Clin Dermatol 2012;30(6):592-598.

4. Baddley JW, Sankara IR, Rodriquez JM, Pappas PG, Many WJ. Histoplasmosis in HIV-infected patients in a southern regional medical center: poor prognosis in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2008;62:151-156.

5. Pasqualotto AC, Lana DD, GodoyCSM, et al. Single high dose of liposomal amphotericin BV in human immunodeficiency virus AIDS-related disseminated histoplasmosis: a randomized trial. Clin Infect Dis 2013;77(8):1126-1132.

6. Karimi K, Wheat LJ, Connolly P, et al. Differences in histoplasmosis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in the United States and Brazil. J Infect Dis 2002;186(11):1655-1660.

7. Sun NZ, Augustine JJ, Gerstenblith MR. Cutaneous histoplasmosis in renal transplant recipients. Clin Transpl 2014;28(10):1069-1074.

8. Assi M, Martin S Wheat LJ, et al. Histoplasmosis after solid organ transplant. Clin Infect Dis 2013;57(11): 1542-1549.

9. Kauffman CA, Freifeld AG, Andes DR, et al. endemic fungal infections in solid organ and hematopoietic cell transplant recipients enrolled in the Transplant-Associated Infection Surveillance Network (TRANSNET). Transpl Infect Dis 2014;16:213-224.

10. Miller AC, Arakkal AT, Koeneman SH, et al. Frequency and duration of, and risk factors for, diagnostic delays associated with histoplasmosis. J Fungi 2022;8(5):438. doi:10.3390/jof8050438.

11. Butt AA, Carreon J. Histoplasma capsulatum sinusitis. J Clin Microbiol 1997;35(10):2649-2650.

12. Nabet C, Belzunce C, Blanchet D, et al. Histoplasma capsulatum causing sinusitis: a case report in French Guiana and review of the literature. BMC Infect Dis 2018;18(1):595. doi:10.1186/s12879-018-3499-5.

13. Khan AR, Raza A, Firasat S, Abid A. CYP3A5 gene polymorphisms and their impact on dosage and trough concentration of tacrolimus among kidney transplant patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacogenomics J 2020;20(4):553-562.