Title: Beneath the Surface – Imported Eumycetoma in a Recent East African Immigrant to Alberta, Canada

Submitted by: Ima Anugom MD1, Brittany Kula MD2, Vanessa Fawcett MD3, Mao-Cheng Lee MD1,4, Justin Bateman MD1, Tanis C. Dingle, Ph.D1, 5

Institution:

- Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada

- Department of Medicine, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada

- Department of Surgery, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada

- Alberta Precision Laboratories, Edmonton, AB, Canada

- Alberta Precision Laboratories, Calgary, AB, Canada

Email: anugom@ualberta.ca

Date Submitted: September 9, 2025

History:

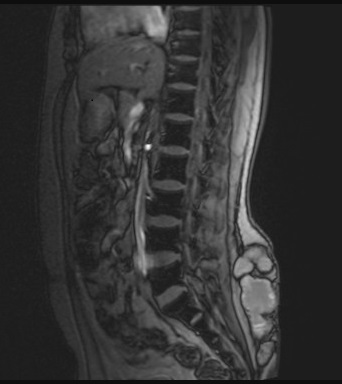

A 26-year-old otherwise healthy man, originally from Ethiopia and having recently immigrated from Kenya to Canada, presented with increasing pain, swelling, and discharge from a chronic wound to his lower back. The symptoms had persisted for years following childhood trauma from falling into a well. No formal wound care was sought at the time, and he experienced chronic discomfort and intermittent drainage. He had no other significant past medical history and was not immuno-compromised. He underwent multiple debridement and antibiotic courses in Kenya without resolution. Nine months after arriving in Canada, he presented to an emergency department for worsening symptoms. Three months prior to his emergency visit, he was evaluated by his family physician, and underwent MRI imaging, which revealed a multiloculated subcutaneous collection without bony involvement measuring 11.6cm x 11.8cm x 3.7 cm (Fig 1A). He received clarithromycin for a presumed chronic hematoma or seroma. However, symptoms persisted, prompting his presentation to acute care.

Physical Examination:

There was a markedly inflamed, indurated area to the right of the midline of the lower back, with multiple areas of fluctuance, sinus tract formation, and serosanguinous drainage (Fig 1B). No regional lymphadenopathy was noted. He was afebrile and hemodynamically stable.

Laboratory Examination:

Routine labs showed mild anemia and slightly elevated C-reactive protein (CRP). Liver enzymes and renal function were within normal limits.

Question 1: What are probable/possible diagnoses?

Possible differential diagnoses include bacterial abscess, fungal infection, chronic seroma/hematoma, cutaneous tuberculosis, soft tissue neoplasm.

Microbiology/Diagnostic Tests Performed:

Imaging: MRI and CT of the lesion revealed a multiloculated subcutaneous collection without bony involvement.

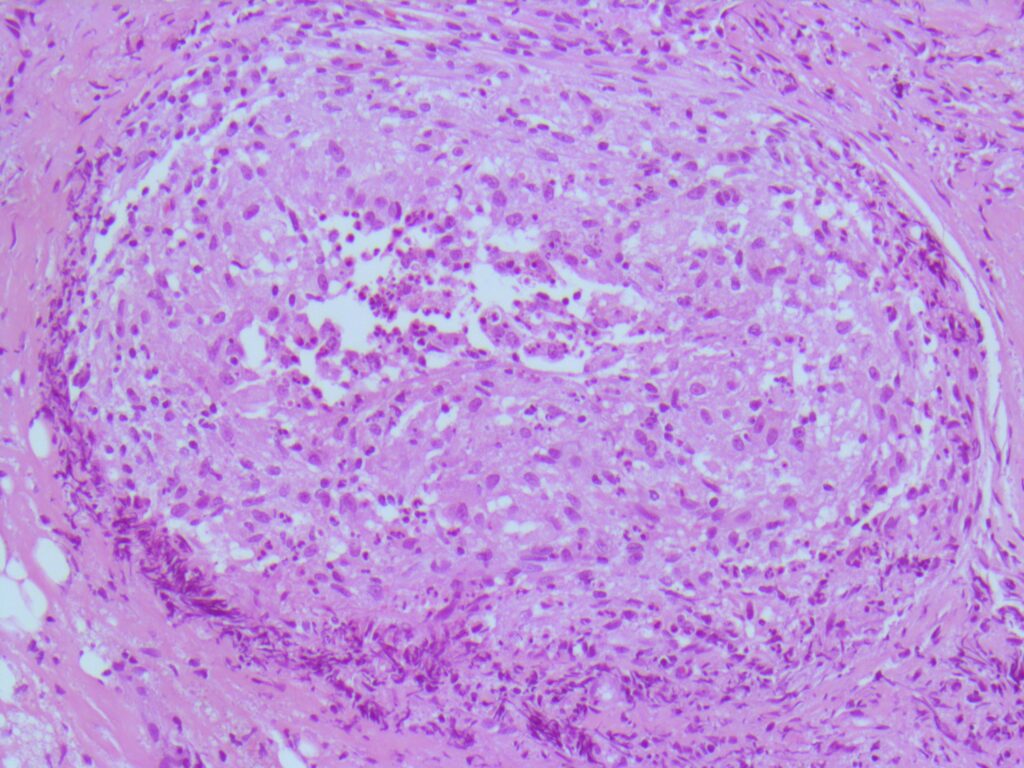

Histopathology: Evaluation using H&E and GMS staining revealed granulomatous inflammation (Fig 2), with septate, acutely branching fungal hyphae embedded in fibrinous material.

Microbiology:

Bacterial cultures: Initial superficial swabs isolated methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA), resistant to clindamycin. Deep wound culture of an intra-operative swab of the lower back isolated 1+ of Cutibacterium acnes susceptible topenicillin, after additional incubation.

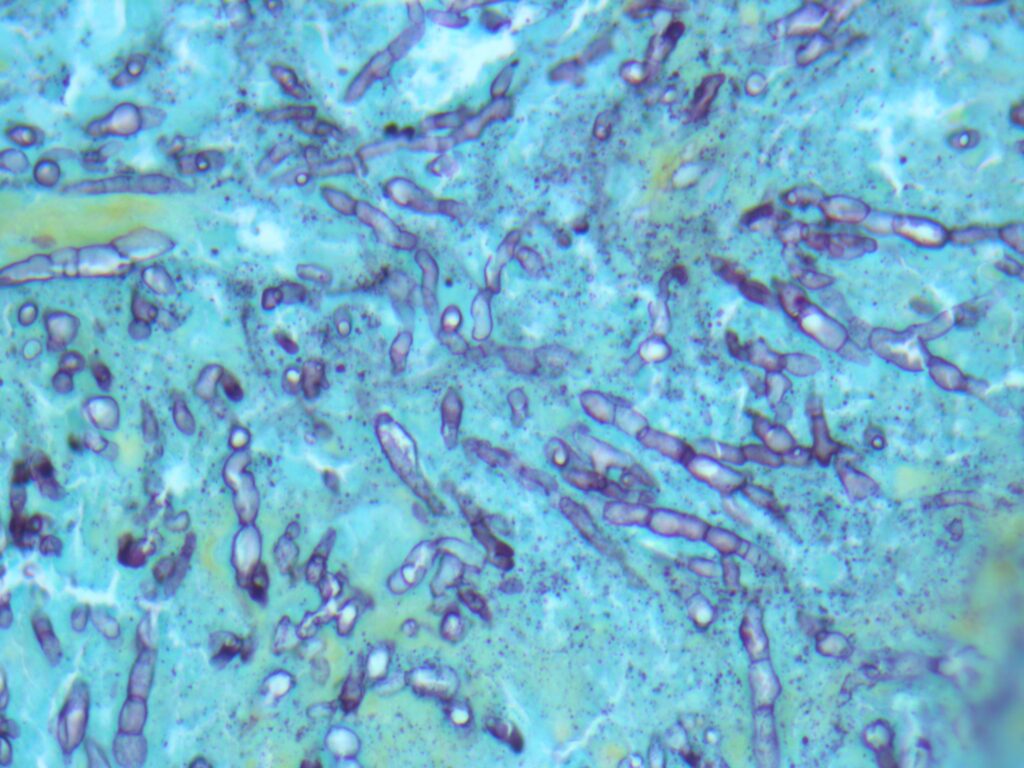

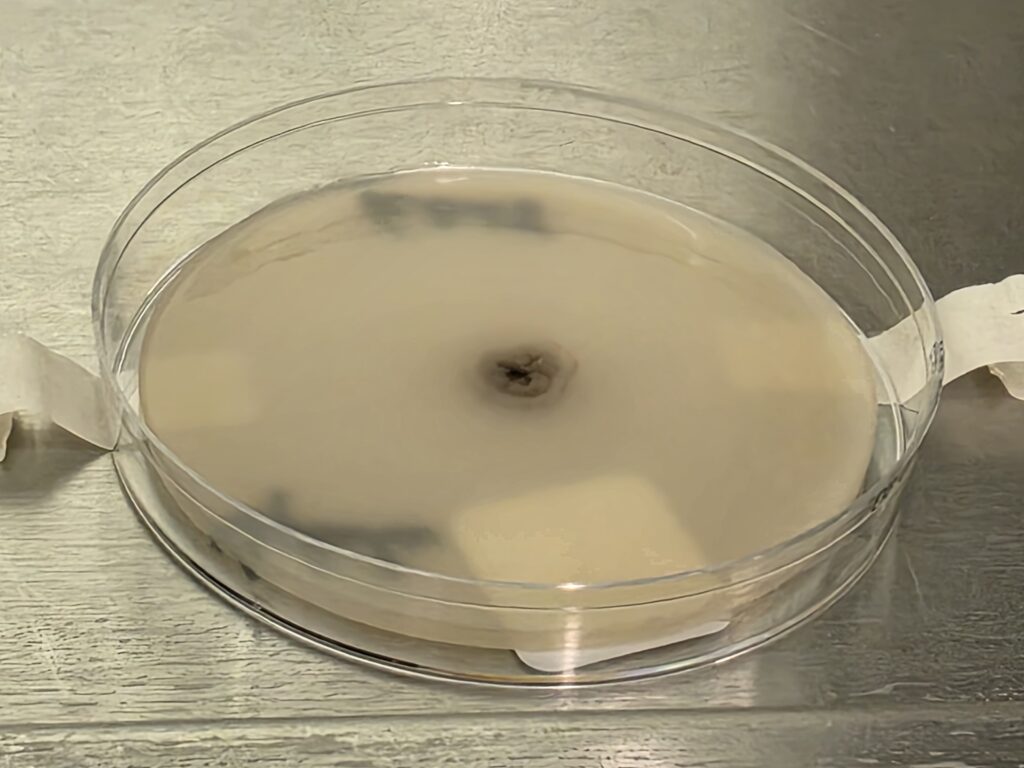

Fungal cultures: Direct exam of lower back intra-operative swabs using Calcofluor white were negative. Gram and KOH stain of crushed granules showed a fungal element. After day 14 of incubation, fungal cultures grew filamentous fungi with the following findings:

- PDA: Tiny white to gray wrinkled colonies with a dark center; dark reverse. (Fig 3A)

- PYE: Small, wrinkled, convoluted, dark colonies with diff brown pigment, with better growth at 35°C; dark reverse.

- Inhibitory Mold Agar: Good growth, light brown, glabrous colonies with red/brown reverse

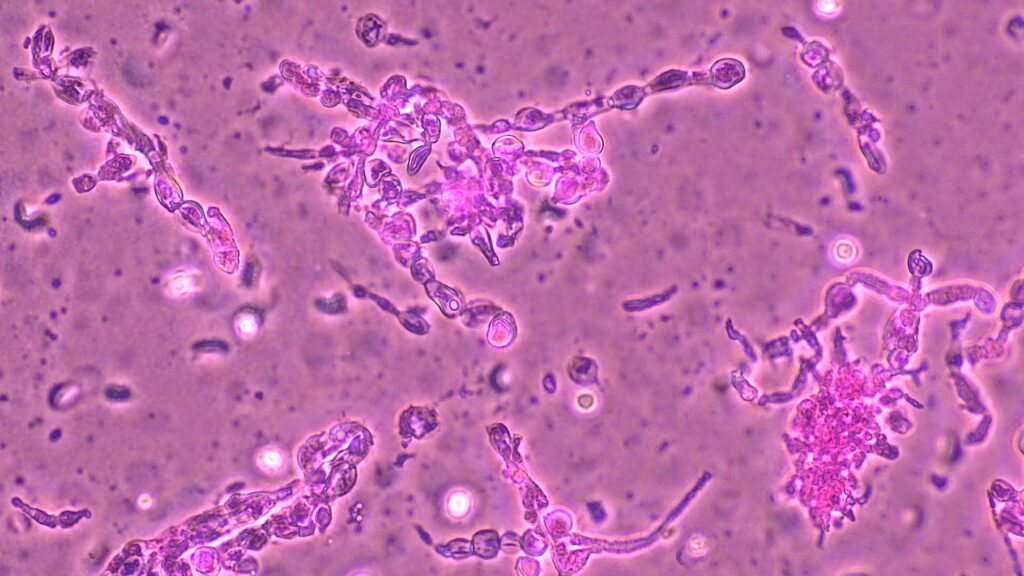

- Tape mount: Short septate hyphae (some thin, with dark pigment) with toruloid forms and abundant chlamydospores (Fig 4)

- Sabouraud Dextrose Agar with antibiotics: No growth

- Sabouraud Dextrose Agar – Thick: One tiny colony

- Urease: Negative

Fungal cultures of back tissue revealed similar findings, with filamentous fungi growing after 16 days.

Mycobacterial cultures also revealed filamentous fungal growth after incubation. Growth was first detected from the lower back swab cultures at 3 and 53 days, while growth was detected from the back aspirate cultures after 13 days incubation.

Fungal sequencing of the isolate using internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region sequencing identified Madurella mycetomatis.

Final Diagnosis:

Eumycetoma caused by Madurella mycetomatis

Question 2: What treatment is recommended in the care of this patient?

Treatment:

A combination of antifungal therapy and surgical debridement with ongoing therapeutic monitoring is recommended.

This patient underwent surgical debridement. Intraoperatively, significant purulent material and numerous small black grains were noted initially suspected to be debris/contamination. He received initial empirical treatment with IV cefazolin 2g q8h and metronidazole 500mg PO TID post-operatively. Given high suspicion for a fungal infection, he was discharged on itraconazole 200 mg PO BID and amoxicillin 500 mg PO TID pending final diagnosis. Amoxicillin was discontinued after one month following confirmation of fungal etiology. Itraconazole trough levels were monitored with ongoing monitoring of CBC, Cr, and ALT. The patient’s dose was later reduced to 100 mg PO BID due to supratherapeutic levels> 3ug/ml, as trough levels >3–4 µg/mL are associated with increased risk of hepatotoxicity (1).

Outcome:

Patient is stable and continues itraconazole therapy. The only reported side effects were nausea and abdominal discomfort. Although the patient had no elevated liver enzymes, a subsequent decline in ALT was noted following dose reduction of itraconazole. A repeat CT imaging showed some improvement of his subcutaneous multiloculated collections. A repeat, but more extensive, surgical revision is planned to optimize clinical outcome.

Discussion:

Mycetoma is a chronic granulomatous infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissue caused by bacteria (actinomycetoma) or fungi (eumycetoma) (2,3,4). Transmission occurs through traumatic inoculation (5,6). Outdoor activities and occupations involving frequent exposure to soil, such as farming and herding, are associated with increased risk (5). Extremities are mostly affected, though lesions may appear in areas like the shoulder and back (5). While it is endemic to tropical and subtropical regions, cases may emerge in non-endemic countries due to global migration (7,8,9).

This case presents a rare instance of eumycetoma in Canada in a patient who immigrated from East Africa, a mycetoma-endemic area, presenting with chronic lower back swelling, drainage, and pain, initially misdiagnosed as a chronic seroma or abscess. Trauma history with prolonged, progressive local symptoms, should raise suspicion for a chronic infectious etiology, particularly in patients from endemic regions. Imaging studies revealed multiloculated subcutaneous collections, but definitive diagnosis required surgical exploration and tissue sampling. Histopathology, fungal culture, and molecular sequencing confirmed Madurella mycetomatis, the most common cause of eumycetoma worldwide.

Despite classic presentation with grains and sinus tracts, eumycetoma is often misdiagnosed due to limited diagnostic access in endemic regions and poor awareness in non-endemic settings (7,10). Delayed diagnosis can result in extensive tissue destruction and disability (7). Fungal culture and histopathology remain essential for diagnosis, though culture requires prolonged incubation (9,11). While molecular methods like ITS sequencing are crucial for definitive species identification of cultured isolates, direct testing of clinical specimens with real-time PCR offers significantly faster diagnosis compared to traditional culture-dependent methods (12)

Madurella mycetomatis is typically resistant to standard antibacterial therapy. Antifungal treatment, often with itraconazole or posaconazole, and repeated surgical debridement are standard management strategies (13).

Itraconazole is the preferred antifungal for eumycetoma, though treatment courses are prolonged (6,13,14). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends 9–12 months of antifungal therapy, though cure rates with antifungal treatment alone remain low (14). Several case series have reported improved outcomes with combined surgical and medical therapy, although relapses are frequent (6). Drug level monitoring is critical, as supratherapeutic levels are associated with hepatotoxicity (1). This patient experienced elevated itraconazole trough levels and required dose adjustment although his liver enzymes were not elevated; they did however decrease with dose reduction. He also reported mild gastrointestinal side effects.

Surgical management remains an essential adjunct to antifungal therapy. Literature supports that preoperative antifungal therapy may encapsulate lesions, facilitating more effective resection (9). Combined medical and surgical approaches yield better outcomes than either modality alone. Nonetheless, recurrence is common, and there is limited guidance on optimal treatment duration or monitoring (10).

This case underscores the diagnostic complexity of eumycetoma in both endemic and non-endemic regions and the critical need for clinician awareness, especially when managing immigrants from high-risk areas. The protracted disease course and initial misdiagnosis reflect the difficulty in recognizing this neglected tropical infection. It also underscores the importance of detailed travel and migration history, especially in patients presenting with chronic soft tissue infections in non-endemic areas. Familiarity with mycetoma and timely use of diagnostic tools can reduce misdiagnosis and improve outcomes.

References:

- Patterson TF et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(4):e1-e60.

- Reis CM, Reis-Filho EG. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:8–18.

- van de Sande WWJ. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7(11):e2550.

- Zijlstra EE et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(1):100–12.

- Fahal AH et al. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2018;3:97.

- WHO. Mycetoma as an NTD. https://www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2016

- Efared B, et al. BMC Clin Pathol. 2017 Feb 2;17:1..

- Siddig, E. E., & Ahmed, A. IJID One Health, 5, 100048.

- Nenoff P et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(10):1873–83.

- Emmanuel P, et al. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2018 Aug 10;17(1):35.

- Alam K et al. J Glob Infect Dis. 2009;1:64–7.

- Arastehfar A et al (2020). PLoS Negl Trop Dis 14(1):e0007845

- ESCMID and ECMM joint clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and management of systemic phaeohyphomycosis: diseases caused by black fungi

- CDC. Mycetoma. https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/mycetoma/