Title: Relapsing Candida meningitis in a diabetic patient

Submitted by: James Dickey, Jose Vazquez

Institution: Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University

Email: jadickey@augusta.edu

Date Submitted: 9/13/2022

History:

A 41-year-old man with past medical history of diabetes mellitus type II, osteomyelitis s/p right above knee amputation, myocardial infarction s/p AICD placement, and hypertension presented with a three-day history of worsening headaches, photophobia, fever, and right hip pain. His symptoms began one day after receiving an epidural steroid injection to the midback, which he received bimonthly at an outside pain management clinic. Vital signs on presentation to the emergency department were significant for temperature 38.5 C. Physical exam was notable for nuchal rigidity and positive Jolt test without photophobia. The patient’s middle and lower back were nontender to palpation without erythema, induration, or fluctuance. Initial labs were notable for a WBC of 28,500/µl. Lumbar puncture revealed a CSF with a grossly cloudy appearance, a WBC of 6,725/µl, with 80% neutrophils, a protein 177 mg/dl, and a relatively depressed glucose at 150 mg/dl (serum glucose 388 mg/dl). CT and MRI were unremarkable, but did reveal degenerative changes of the lumbar spine but no abscess or fluid collection. The patient was initiated on empiric vancomycin and ceftriaxone for suspected bacterial meningitis. His symptoms gradually resolved over the following week, and his blood and CSF cultures were negative. In view of the recent epidural injections and a history of multiple previous PICC lines, the patient was prescribed a two-week course of linezolid on discharge of which the patient only completed a three day course. On outpatient follow-up two wks later, the patient was asymptomatic, and linezolid was not resumed.

However, one month following the initial hospitalization, the patient again presented to the emergency department complaining of a two-week history of worsening band-like headaches, sweats, chills, and anxiety.

Physical Examination:

Temp 38.4 C; HR 102/min; RR 16/min; BP 167/138 mmHg

General: No acute distress. Well nourished, well developed, appears stated age.

HEENT: EOMI, funduscopic examination was unremarkable.

Neck: Trachea midline without mass. Full range of motion without any nuchal rigidity.

Cardiovascular: RRR, no murmurs, rubs or gallops, no peripheral edema.

Respiratory: Clear to percussion and auscultation.

Gastrointestinal: Soft, non-tender, non-distended, no masses, no hepatoslenomegaly.

Musculoskeletal: No gross deformities appreciated. Minimal tenderness to palpation over the L5 area. Full range of motion of all extremities. Right prosthetic leg from a previous AKA.

Dermatologic: Warm, dry. No rashes.

Neurologic: Alert and oriented to person, place, and time. GCS 15. CN II-XII intact. Sensation grossly intact. Strength 5/5 in bilateral UE and LE. Finger to nose intact bilaterally. No pronator drift.

Laboratory Examination:

WBC: 12,300/µl, ESR: 36/mm, CRP: 2.234, Serum Glucose: 229 mg/dl

Radiology: CT Abdomen/Pelvis with contrast: No loculated fluid collection to suggest abscess, no acute fracture or dislocation of the visualized spine.

MRI Lumbar Spine w/ Contrast: No evidence of discitis/myelitis/epidural abscess.

Question 1: What are probable/possible diagnoses?

Given the negative CSF cultures from the previous hospitalization, the differential diagnosis at this stage ranged from an aseptic meningitis with underlying viral etiology including Mollaret’s meningitis, a fungal infection originating from the routine spinal injections, or a non-infectious etiology in the setting of chronic NSAID use. Bacterial infection was deemed less likely given his hemodynamic stability and his unresponsiveness to prior broad antibacterial empiric therapy.

Microbiology/Diagnostic Tests Performed:

- CSF Analysis:

WBC: 2425/µl with 81% polysegmented neutrophils,

RBC: 1

Protein: 192 mg/dl

Glucose: 22 mg/dl (serum glucose 216/mg/dl).

CSF Cryptococcal antigen: Negative

CSF HSV PCR: Negative

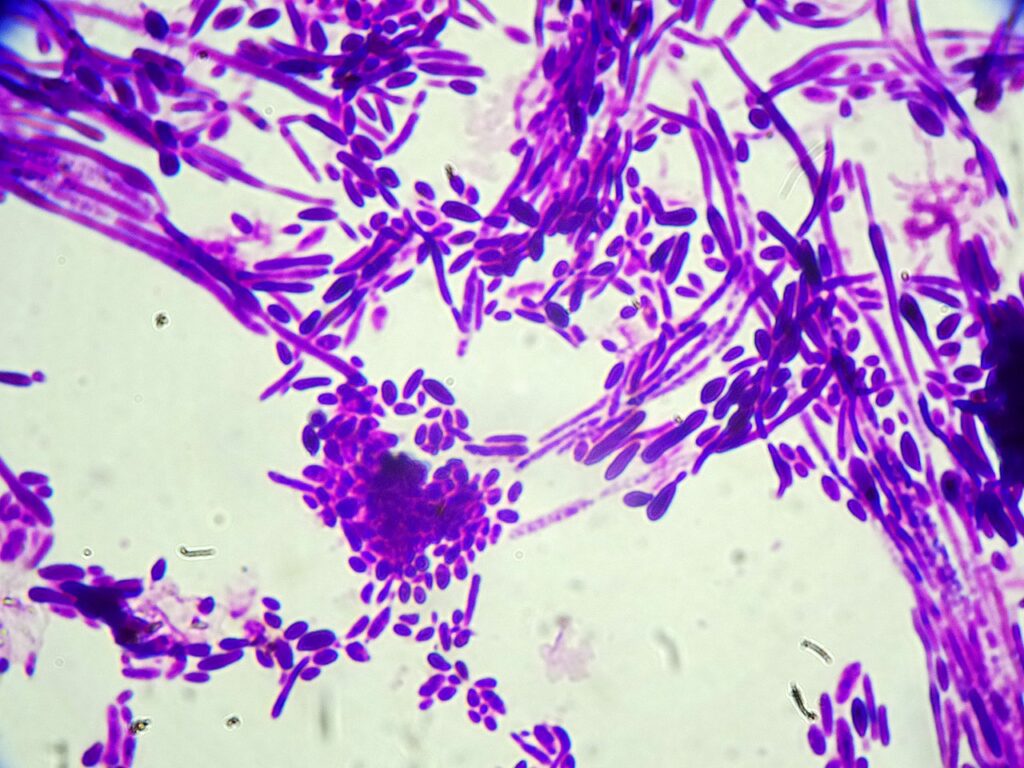

- Before CSF culture result was finalized, budding yeast were noted on the CSF hematology slide for cell count, prompting the initiation of empiric antifungal treatment with micafungin before the CSF culture was finalized.

- Final CSF Culture: Candida dubliniensis

Final Diagnosis: Candida dubliniensis meningitis

Question 2: What treatment is recommended in the care of this patient?

Treatment: Treatment was initiated with IV liposomal amphotericin B (LAMB) 5mg/kg and PO flucytosine 25mg/kg four times a day as induction therapy x 10 days. On day six of treatment, amphotericin B dose was decreased to 3mg/kg due to worsening renal function. Repeat lumbar puncture on day seven of treatment demonstrated CSF clearance of yeast and a resolving pleocytosis to 593/µl. After completing 10 days of combination therapy and clinical resolution of symptoms, the patient was discharged home on four wks oral fluconazole 400mg daily.

Outcome:

On follow-up with his primary care physician two wks after discharge, the patient reported no complaints. However, three months later the patient again presented to the emergency department complaining of a four-day history of worsening fever, nausea, chills, headache, photophobia, and nuchal rigidity. Vitals were notable for a temperature 39.3 C, heart rate 102/min, and blood pressure 172/91 mmHg. Gram stain of lumbar puncture showed multiple budding yeast, later confirmed to be Candida dubliniensis on culture. The patient was again initiated on amphotericin B and flucytosine. The patient’s symptoms improved with a ten-day course of liposomal amphotericin B and flucytosine. The dose of amphotericin B was again reduced to 3mg/kg on day seven of treatment due to worsening renal function. A repeat lumbar puncture on day 10 again demonstrated CSF sterilization. This time, the patient was discharged on a 12-week course of fluconazole 400mg daily.

Over the next 12 wks, the patient presented to multiple outpatient follow-ups with no headaches or recurrence of his symptoms. However, four wks after finishing his 12-week course of fluconazole, he again presented to the emergency department complaining of intense generalized headaches without nuchal rigidity. In consultation with the infectious disease team it was decided to discharge the patient from the emergency department on 800mg fluconazole daily. Since then, the patient has remained on this regimen without recurrence of his meningitis symptoms or complications from medication.

Discussion:

Candida species are an uncommon cause of meningitis in adults, typically occurring as a manifestation of disseminated candidiasis or as a complication from neurosurgical procedures [1,2]. Chronic isolated infections are rare but well documented [1,3,4]. Candida albicans remains the most common causative pathogen of meningitis among Candida species, while few cases of invasive Candida dubliniensis infections have been reported [4-8].

Aside from this patient’s uncontrolled diabetes increasing his risk of infection, he was otherwise immunocompetent with no recent neurosurgery or evidence of disseminated infection. While other sources cannot be entirely ruled out, it is plausible that the regular steroid injections into his back were the likely cause of his infection. In 2012, an outbreak of fungal meningitis in the US that was linked to contamination of methylprednisolone injections which resulted in 753 cases and 64 deaths [9]. In the absence of additional cases of invasive Candida infection in patients receiving steroid injections, this source of infection is unlikely for our patient. It is likely that C. dubliniensis was colonizing the skin and was carried via the needle leading to direct inoculation of the spinal and paraspinal tissues.

The delay in diagnosis caused by the lack of recovery of C. dubliniensis from the CSF culture is not surprising given similar difficulties in previously reported cases of Candida meningitis [5-8,10]. However, our patient demonstrated clear neurologic symptoms one day after his steroid injection with accompanying findings on the CSF. We suspect the patient developed an acute inflammatory response that resolved over the following days as he was inadvertently treated for presumed bacterial meningitis. The infectious burden due to Candida was likely too low to be recovered on gram stain and culture at the initial presentation. Since he was only treated with antibiotics during the first hospitalization, the fungal infection progressed subacutely leading to his second hospitalization several months later.

The multiple recurrences of this patient’s infection with interspersed asymptomatic periods demonstrates the difficultly in treating Candida meningitis. To date there have been no clinical trials to evaluate treatment for CNS candidiasis, and treatment guidelines are based on reported cases and small case series. IDSA/MSGERC guidelines from 2016 recommend initial treatment with liposomal AmB with or without flucytosine, followed by fluconazole as step down therapy. Step down therapy should continue until all signs and symptoms, CSF abnormalities, and radiologic abnormalities have resolved [2]. However, the duration of therapy is not specified.

Secondly, it is important to note that the patient had a prior history of medication nonadherence. In fact, it is probable that non-adherence with step-down fluconazole likely contributed to the relapsing infection and the persistence of the Candida infection which necessitated repeated treatments. He did admit to poor compliance with the 12-week course of fluconazole after his third hospitalization, and we suspect nonadherence may have been a factor during the initial 4-week course of fluconazole, following the initial diagnosis of C. dubliniensis meningitis. Chronic Candida CNS infections are difficult to clear even with complete adherence to therapeutic regimens. To what degree treatment failures were caused by the difficult pharmacodynamics of infection and by medication nonadherence is uncertain. Regardless, the patient currently reports complete adherence to the maintenance fluconazole 800mg daily over the past year. He has not reported any manifestations of recurrent meningitis.

Key References:

1. Sánchez–Portocarrero J, Pérez–Cecilia E, Corral O, Romero–Vivas J, Picazo JJ. The central nervous system and infection by Candida species. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 2000;37(3):169-179. doi:10.1016/s0732-8893(00)00140-1

2. Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Candidiasis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2015;62(4):e1-e50. doi:10.1093/cid/civ933

3. Voice RA, Bradley SF, Sangeorzan JA, Kauffman CA. Chronic Candidal Meningitis: An Uncommon Manifestation of Candidiasis. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1994;19(1):60-66. doi:10.1093/clinids/19.1.60

4. Bourbeau K, Gupta S, Wang S. Candida albicans meningitis in AIDS patient: A case report and literature review. IDCases. 2021;25:e01216. doi:10.1016/j.idcr.2021.e01216

5. Herrera S, Pavone P, Kumar D, et al. Chronic Candida dubliniensis meningitis in a lung transplant recipient. Medical Mycology Case Reports. 2019;24:41-43. doi:10.1016/j.mmcr.2019.03.004

6. Gheshlaghi M, Helweg-Larsen J. Fatal chronic meningitis caused by Candida dubliniensis after liver transplantation. Medical Mycology Case Reports. 2020;27:22-24. doi:10.1016/j.mmcr.2019.12.009

7. Tahir M, Peseski AM, Jordan SJ. Case Report: Candida dubliniensis as a Cause of Chronic Meningitis. Frontiers in Neurology. 2020;11. doi:10.3389/fneur.2020.601242

8. Yamahiro A, Lau KHV, Peaper DR, Villanueva M. Meningitis Caused by Candida Dubliniensis in a Patient with Cirrhosis: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Mycopathologia. 2016;181(7-8):589-593. doi:10.1007/s11046-016-0006-7

9. Multistate Outbreak of Fungal Meningitis and Other Infections . CDC. Published April 23, 2019. Accessed September 5, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/hai/outbreaks/meningitis.html

10. Baldwin K, Whiting C. Chronic Meningitis: Simplifying a Diagnostic Challenge. Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports. 2016;16(3). doi:10.1007/s11910-016-0630-0