Overview

As discussed in the section on candidemia, an intravascular catheter is probably the most important and frequent removable source of Candida spp. in the bloodstream of both adults and children [518, 1308, 1904, 1967, 2411]. Once the organism reaches the catheter (direct contamination and transient fungemia from a gastrointestinal source are two possibilities), it adheres to and propagates on the surface of the catheter or the surrounding fibrin clot. In so doing, a large nidus of infection is produced. However, the label “catheter-related” is sometimes taken to imply that the candidemia is trivial. This is not, however, uniformly the case. Catheter-related fungemia tends to be of high density and seeding may occur [207, 341, 1600, 1967]. Indeed, as discussed in (A): Candidemia/Therapies, it is generally believed that all candidemic patients should be treated with an antifungal agent [1915]. In addition, all candidemic patients should have a dilated ophthalmologic examination (for details see candidal endophthalmitis). In the absence of symptoms, studies of other sites of potential spread (e.g., examination of heart values by echocardiography) are not warranted. Conversely, candidemia that persists following catheter removal should prompt studies to rule out endocarditis and septic thrombosis [1860].

Given the above, the physician’s decision regarding catheter removal is probably as important as the choice of drug therapy. Catheter removal has been proposed as part of the standard therapeutic approach for this condition [518, 649, 1224, 1308, 1903]. This recommendation specifically refers to removing all lines and avoiding insertion of new lines by a guidewire exchange from an old line[1903].

However, the influence of catheter removal on the resolution of candidemia has been only partially evaluated and it seems to vary with the patient group. The biggest difference appears to be that between neutropenic and non-neutropenic patients. In reviewing these data, it is also important to realize that the recommendations are derived almost exclusively from observational information. Althought data appear to make a compelling case for the benefit of catheter removal in non-neutropenic patients, the data are weaker for neutropenic patients [71, 1915]. For a better understanding of this controversial issue, we will review the available data in detail.

Catheter Removal in Non-Neutropenic Patients

In non-neutropenic patients, catheter removal has repeatedly been correlated with more rapid clearance of the bloodstream and/or better prognosis [71, 518, 676, 1903]. As an example of the available data, Dato et. al retrospectively reviewed 31 cases of catheter-related candidemia in a large pediatric hospital [518]. There was a trend towards poorer prognosis when catheters were retained, while catheter removal seemed to favor lack of complications. However, the numbers were small.

In the same publication, Dato et. al reviewed the literature on catheter-related candidemia published after 1975. In this analysis they excluded case reports and pooled together studies describing cases of catheter-related candidemia where treatment and outcomes were described. These patients were classified in three groups according to the therapeutic strategies and generated these data:

| Therapeutic Intervention | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Catheters removed No Amphotericin B |

Catheters removed plus Amphotericin B |

Catheters retained plus Amphotericin B |

|

| Number of Patients | 20 | 26 | 25 |

| Cures | 14 | 23 | 14 |

| Failures (Death) | 6(1) | 3(1) | 11(3) |

| Cure rate (%) | 70 | 88 | 56 |

| Mortality rate (%) | 5 | 4 | 12 |

| Therapeutic Intervention | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Catheters removed No Amphotericin B |

Catheters removed plus Amphotericin B |

Catheters retained plus Amphotericin B |

|

| Number of Patients | 20 | 26 | 25 |

| Cures | 14 | 23 | 14 |

| Failures (Death) | 6(1) | 3(1) | 11(3) |

| Cure rate (%) | 70 | 88 | 56 |

| Mortality rate (%) | 5 | 4 | 12 |

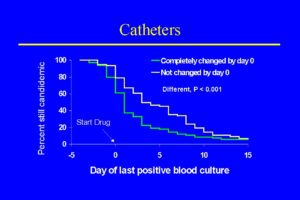

These data favor catheter removal, but they should be approached cautiously. These numbers come from a variety of observational studies and patients with different underlying diseases, ages, and risk factors that were treated with variable amounts and dosage of amphotericin B. Another relevant set of data on catheter removal and candidemia in non-neutropenic patients comes from the randomized trial performed by Rex et al. [1904]. Seventy two percent of candidemia cases in this study were thought most likely related to the presence of an intravascular catheter. A specific analysis of the advantage of removing and replacing all catheters in 206 patients enrolled in this study, demonstrated a significant reduction in the duration of candidemia from 5.6 to 2.6 days [1903]. The impact of complete catheter removal easily seen in the figure [1903].

Catheter Removal in Neutropenic Patients

As opposed to the previously discussed population, there is evidence that the gut may more frequently be a prominent source of candidemia in neutropenic patients, especially if they have mucositis [460, 549]. It has been postulated that circulating yeast attach to the intravascular catheter and thus create a continuous focus of seeding into the bloodstream [1308]. Therefore, the catheter may be both the source and the target of candidemia. In both cases, removing the catheter may help to clear one focus of infection. But, if a cancer patient had a significant and persistent gastrointestinal source of candidemia, catheter removal would be expected to be only partially successful.

As an example of this possibility, Lecciones et. al evaluated retrospectively 155 episodes of catheter-related candidemia in cancer patients [1308]. About two thirds of these patients were neutropenic and the large majority (92%) had their catheter removed as part of therapy. Treatment with antifungal therapy alone was associated with a worse prognosis. Based on these findings, the authors recommended catheter removal as part of the management of candidemia. However, the number of patients in whom catheters were not removed was very small (11 patients).

Perhaps more useful is a study in which Anaissie et al. retrospectively evaluated the impact of central venous catheter removal on the outcome of 416 candidemic cancer patients [71]. When catheter exchange was examined in relationship to the time of initiation of antifungal therapy, complete catheter exchange did improve outcome slightly (P values were 0.02 to 0.06 for this effect). Very importantly, becoming or remaining neutropenic, APACHE III score, and the presence of documented visceral dissemination were MUCH more important than catheter exchange in predicting outcome.

Finally, Nguyen et al. evaluated prospectively 427 consecutive episodes of candidemia as part of a multicenter observational study [1642]. From this large group, 82 neutropenic patients had evaluable catheter data. Among these patients there was a significant lower mortality among patients who had their catheter removed (11% versus 29%, p < 0.045). So once again, the data favors catheter removal as part of therapy for catheter-related candidemia.

Is it possible to decide if the catheter is infected without removing it?

The above-mentioned difficulties would be considerably eased if it were possible to determine by inspection whether or not a catheter is infected. Indeed, one could argue that the real question is not whether to remove the catheter but which catheter to remove!

Unfortunately, no sure way to identify infected catheters has emerged. Statistical data on the likelihood of a positive tip culture were provided in one analysis and showed that hyperalimentation in the previous 30 days and positive blood culture for C. parapsilosis increased the likelihood of a positive catheter tip, whereas chemotherapy in the previous 30 days and neutropenia at the time of the positive blood culture were associated with a decreased likelihood of a positive tip culture [71]. However, these general observations become less helpful when one is faced with a specific catheter in a specific patient.

However, several general principles do appear true. First, local site care should follow good general practice. The insertion site should be palpated daily. If pain or tenderness develop, then it should be inspected promptly. Second, bloodstream infections with C. parapsilosis are indeed almost always due to a catheter [71, 845]. This organism has an unusual affinity for plastic. Its appearance in the bloodstream should prompt immediate removal of all catheters if at all possible. The third idea is more controversial. Differential quantitative blood cultures of blood obtained through the catheter and then from a peripheral venipuncture site have been proposed as another way of identifying infected catheters [2228]. However, not all authors have found this approach useful [1740]. As the differential quantitative culture method is both more technically demanding and takes time to perform, relatively few centers have implemented this approach. Exchange of possibly infected catheters by use of a guidewire is sometimes helpful as an intermediate approach. While this is not possible with implanted lines, this technique can be useful in patients with limited access. If a culture of the tip of the removed line is positive and/or the patient remains ill, then it will be clear to all that strong efforts to place a new line must be made.

Cost Considerations

Related to the previous discussion, the expense of removing surgically implanted lines (Hickman or Broviac) has also been raised as a consideration [649]. While it is indeed true that catheter removal and re-insertion carries a non-trivial cost, a therapeutic decision of this nature should not be taken based on individual cost considerations. Instead, the best overall care plan will usually result in the lowest overall (global) cost.